By Kyle Davi, Trustees Staff

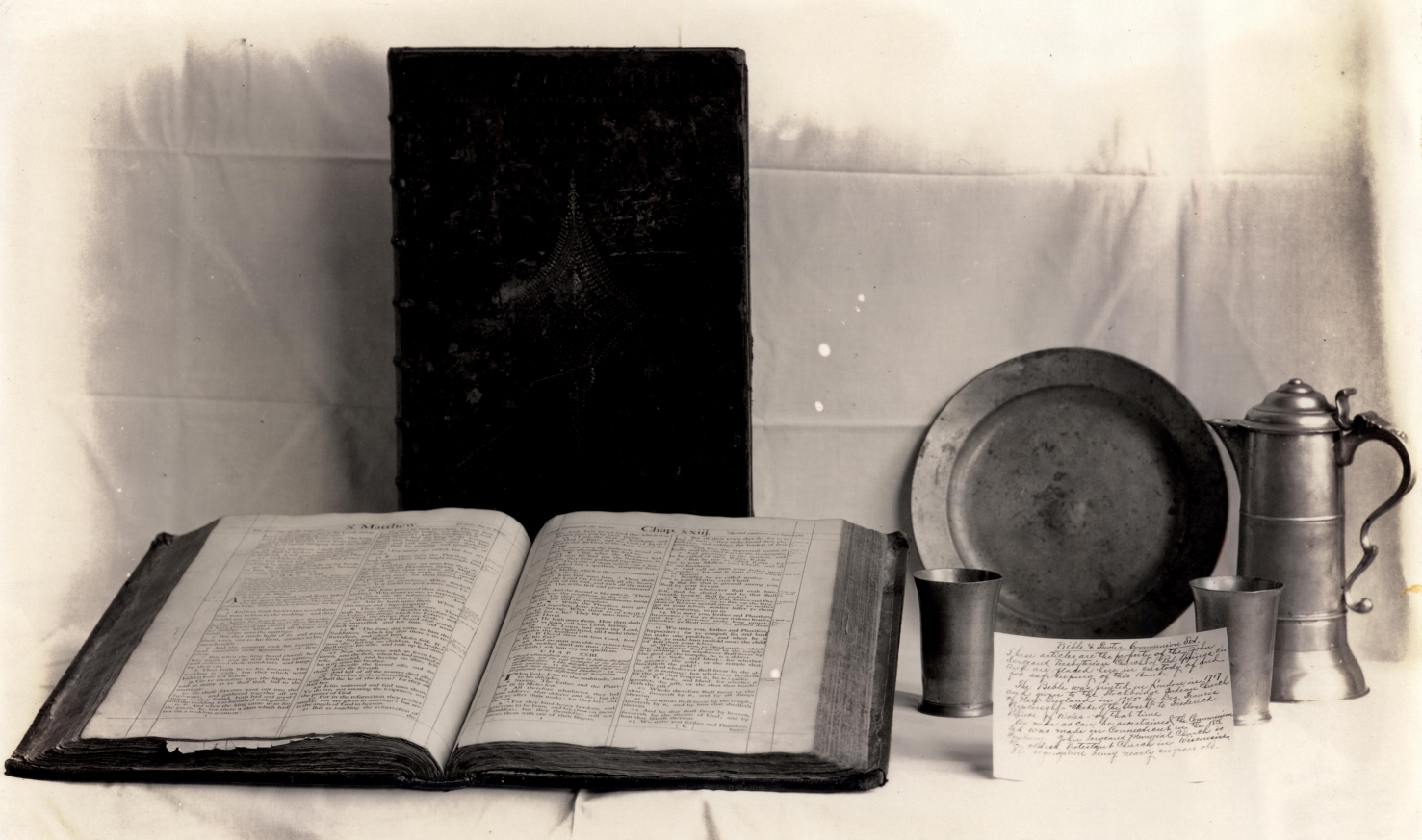

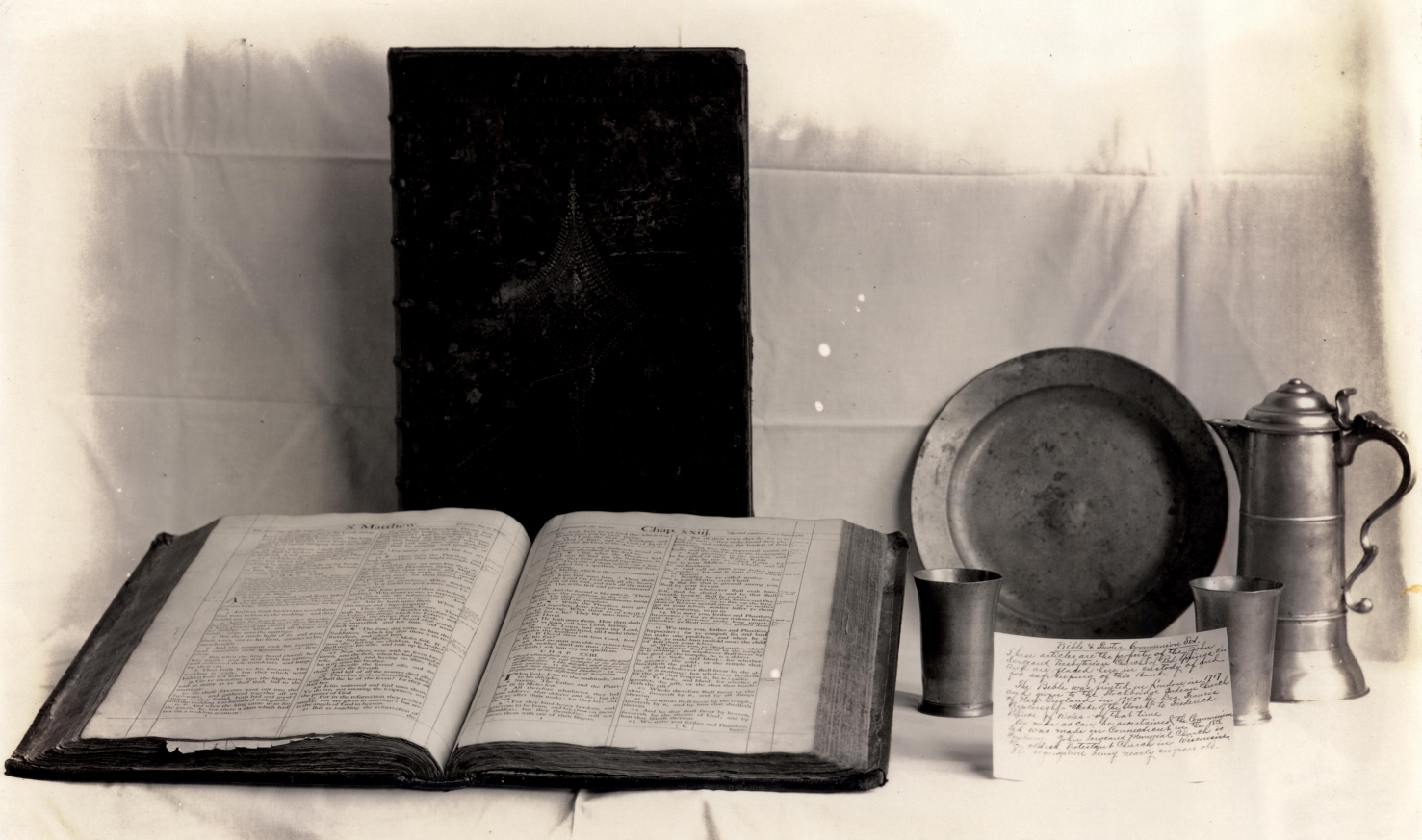

Repatriated Bible volumes and Communion set. Image from the Arvid E. Miller Library/Museum.

This year, a new chapter opened in the 50-year story comprising The Trustees’ commitment to Indigenous communities. One of the most important aspects of this commitment is repatriating—returning an object to its rightful owner—many of the Indigenous artifacts that have come into The Trustees’ possession over the years.

When properties are donated to the organization, the previous owners’ collections housed on those properties are usually gifted as well. Several Trustees places—The Mission House and Fruitlands Museum—came with extensive collections of Native artifacts which had been amassed by Mabel Choate and Clara Endicott Sears respectively. Many of these objects had been purchased from dealers who often acquired them under dubious circumstances.

For many years The Trustees has been committed to identifying and repatriating these objects. From the first dialogues about repatriation to current endeavors to investigate every Native artifact in the organization’s collections, the focus has been on building robust relationships with the communities who are the items’ rightful owners.

“The objects in our collections hold significant cultural meaning to tribal communities,” said Mark Wilson, Trustees Director of Historic Collections and Archives. “We need to make sure they know we have these objects and share all the information we can about what happened to them once they left the tribal community.”

The Trustees has been actively working on repatriating tribal items from its Mission House collection for decades, but Wilson and the team are now spurred on by a revision to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) that went into effect in January 2024. The new regulations implement a forceful “Duty of Care” to all museums, nonprofits, and federal agencies that have Native objects in their collections and grant Indigenous communities a stronger authority throughout the repatriation process.

These new NAGPRA alterations provide a catalyst to take a comprehensive inventory of the substantial collections gifted to The Trustees by Mabel Choate and Clara Endicott Sears (among others).

A Step Ahead

The Stockbridge-Munsee Community's crest flies on a flag at The Mission House.

Since the 1970s—years before NAGPRA went into effect—the organization has been in dialogue with the Stockbridge-Munsee Community about Mabel Choate’s collections at The Mission House. A two-volume Bible set, gifted to the Community in 1745 and preached from by missionary John Sergeant at The Mission House, was the first item returned in 1990, building a foundation of trust and paving the way for future collaborations.

Now 34 years later, nearly three dozen additional objects have been returned to the Stockbridge-Munsee Community, including those of significant religious import like a four-piece pewter Communion set. The return of each item results from years of conversations between Trustees staff and tribal community members.

“Our discussions around the objects in The Trustees collections are always ongoing,” said Wilson. “I’ve personally made two trips to the reservation in Wisconsin to speak with tribal members and have seen the life and vibrancy of the community there.”

Part of that ongoing work includes Our Lands, Our Home, Our Heart—an indoor exhibit, garden of native plantings, and traditional medicine cabinet directly curated by the Stockbridge-Munsee’s Cultural Affairs Department—open at The Mission House this summer. The property’s Carriage House space, where the Community’s exhibit is located, once held Mabel Choate’s collection of Indigenous objects. Now, it’s a place where the Stockbridge-Munsee Community can tell their own story in their own words.

“By listening to tribal members and removing the Indigenous objects previously displayed in the Carriage House, we’ve opened a space where the Community can now share their own voice on their own homelands,” said Wilson.

Continuing to Listen

The view from Monument Mountain.

Listening to, and working with, Indigenous communities has not stopped at the historic collections. Months before the National Park Service began replacing derogatory names of the nation’s geographic features in 2021, The Trustees worked with the Stockbridge-Munsee Community to rename Monument Mountain’s peak.

Previously named Squaw Peak—an ethnic and sexist slur in the Mohican language—its name was changed to “Peeskawso Peak” (pronounced / Pē: skãw. sō /), meaning “virtuous women.” Not only did this renaming allow the Stockbridge-Munsee Community to take back their history and right a wrong, but it also allowed members of the Community to reconnect with this sacred place on their homelands.

“Whether it’s the Mohican people or another Indigenous community, we are on tribal homelands everywhere we go in this organization,” said Wilson. “It’s important that our visitors understand and respect that when visiting any of our places.”

Where We Go From Here

Mark Wilson stands outside "Our Lands, Our Home, Our Heart."

Even with the significant work thus far, The Trustees has a long way to go in building respectful relations with Indigenous communities like the Stockbridge-Munsee. The extensive nature of the historic collections—especially that of Clara Endicott Sears at Fruitlands Museum, which is the Trustees’ largest—makes repatriation challenging.

It’s estimated that just the first step of inventorying every object will be a multi-year process. From there, each item will need to be cataloged with a history of ownership and usage since it left tribal lands, all while dialogues are opened with the multitude of Indigenous communities from across the nation to whom these objects belong.

“We need to be honest about what happened to these objects with the Tribes,” said Wilson. “It’s important we’re upfront about how they were acquired, housed, and displayed as we work to repatriate them to their proper owners.”

The entire process is expected to take at least five years, but the start of the project in 2024 marks a major milestone in the repatriation work done so far by The Trustees. The daunting timeline doesn’t deter Wilson, who will be leading the team in these substantial efforts.

“By doing the inventory, we can understand what we have and how to forge ahead,” said Wilson. “It’s a big step forward for us and I’m excited to be a part of it.”