The Colonel John Ashley House, Sheffield

Standing up in the face of injustice takes extraordinary courage, and two women linked to The Trustees did just that in the fight for freedom and equality. These pioneering crusaders for justice—born nearly a century apart—are now honored by The Trustees by conserving the properties that were once their homes and sharing their stories with the many generations that have followed.

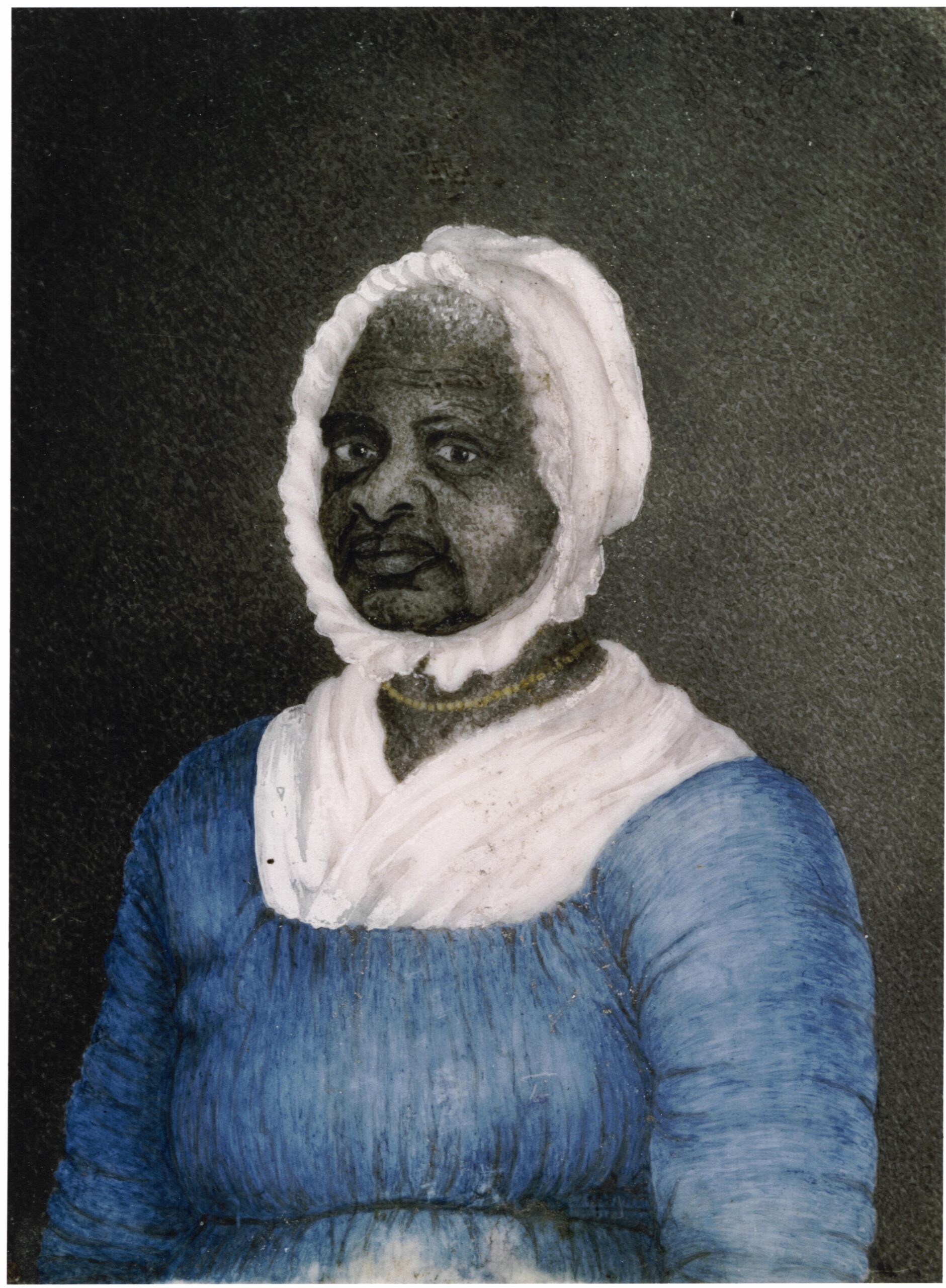

Elizabeth Freeman

Ashley House, Sheffield

“Any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman—I would.”

“Any time while I was a slave, if one minute’s freedom had been offered to me, and I had been told I must die at the end of that minute, I would have taken it—just to stand one minute on God’s earth a free woman—I would.”

These are the words of Elizabeth Freeman (ca. 1744-1829)—also known as Mum Bett—who was born into slavery. She was enslaved by Colonel John Ashley in Sheffield until 1781, when—amid the American Revolution—Freeman and a man named Brom successfully sued for their freedom.

Once free, Freeman chose to work for Theodore Sedgwick, the lawyer who tried her case. She and her daughter Betsy moved to Stockbridge and helped raise the seven Sedgwick children. In 1803, Freeman bought a house and 19-acre farm of her own, where she welcomed her extended family of grandchildren and great-grandchildren and lived out her life as a beloved member of the Stockbridge community.

Lucy Stone

Rock House Reservation, West Brookfield

Leading suffragist and abolitionist Lucy Stone (1818-1893) was born in a farmhouse on Coy’s Hill in West Brookfield (now part of Rock House Reservation). Stone was the first woman in Massachusetts to earn a college degree and organized the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester (1850).

Leading suffragist and abolitionist Lucy Stone (1818-1893) was born in a farmhouse on Coy’s Hill in West Brookfield (now part of Rock House Reservation). Stone was the first woman in Massachusetts to earn a college degree and organized the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester (1850).

When she married, she wrote her own vows, omitting the reference to obedience and insisted on keeping her surname. In 1858, Stone boldly refused to pay property taxes on the basis of “no taxation without representation.” In 1879, she registered to vote in Massachusetts but was removed from the rolls because she did not use her husband’s name.

Stone disagreed with the mainstream women’s suffrage movement over the 14th and 15th Amendments, which guaranteed voting rights regardless of race but not gender. Stone did not see this as a setback for women, but rather a fulfillment of her abolitionist beliefs. She formed the separate American Woman Suffrage Association in 1869 but reunited with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s National Woman Suffrage Association in 1890.

Stone continued to crusade for equality throughout her life, though it was not until nearly 30 years after her death that women received the right to vote nationally with the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. Her dreams for equality for people of color took much longer to realize, however—their right to vote wasn’t guaranteed until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.