Watercolor of Elizabeth Freeman (courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society) inside the Elizabeth Freeman Room at the Ashley House in Sheffield, MA. Photo by David Edgecomb.

In 2011—on the 230th anniversary of Elizabeth Freeman’s landmark legal case that helped abolish slavery in Massachusetts—The Trustees unveiled the Elizabeth Freeman Exhibit at the Ashley House in Sheffield. It remained open to visitors for over a decade, untouched even as new insights into Freeman’s story were uncovered…until this summer.

“As we learned more, it was clear we had to make updates to the exhibition,” said Livy Scott, Curatorial Fellow at The Trustees. “We want to make the Ashley House a space where Elizabeth’s story and the history of slavery in rural Massachusetts are best told in the region.”

Scott spent over a year diving into new primary sources and revisiting archival materials related to the Ashley family and the individuals they enslaved. Her research focused not just on separating fact from fiction within Elizabeth Freeman’s story, but all the stories of those who lived and were enslaved on the property. Now, the Ashley House’s narrative recenters the everyday life of those in bondage and raises awareness about slavery in the North and its enduring consequences.

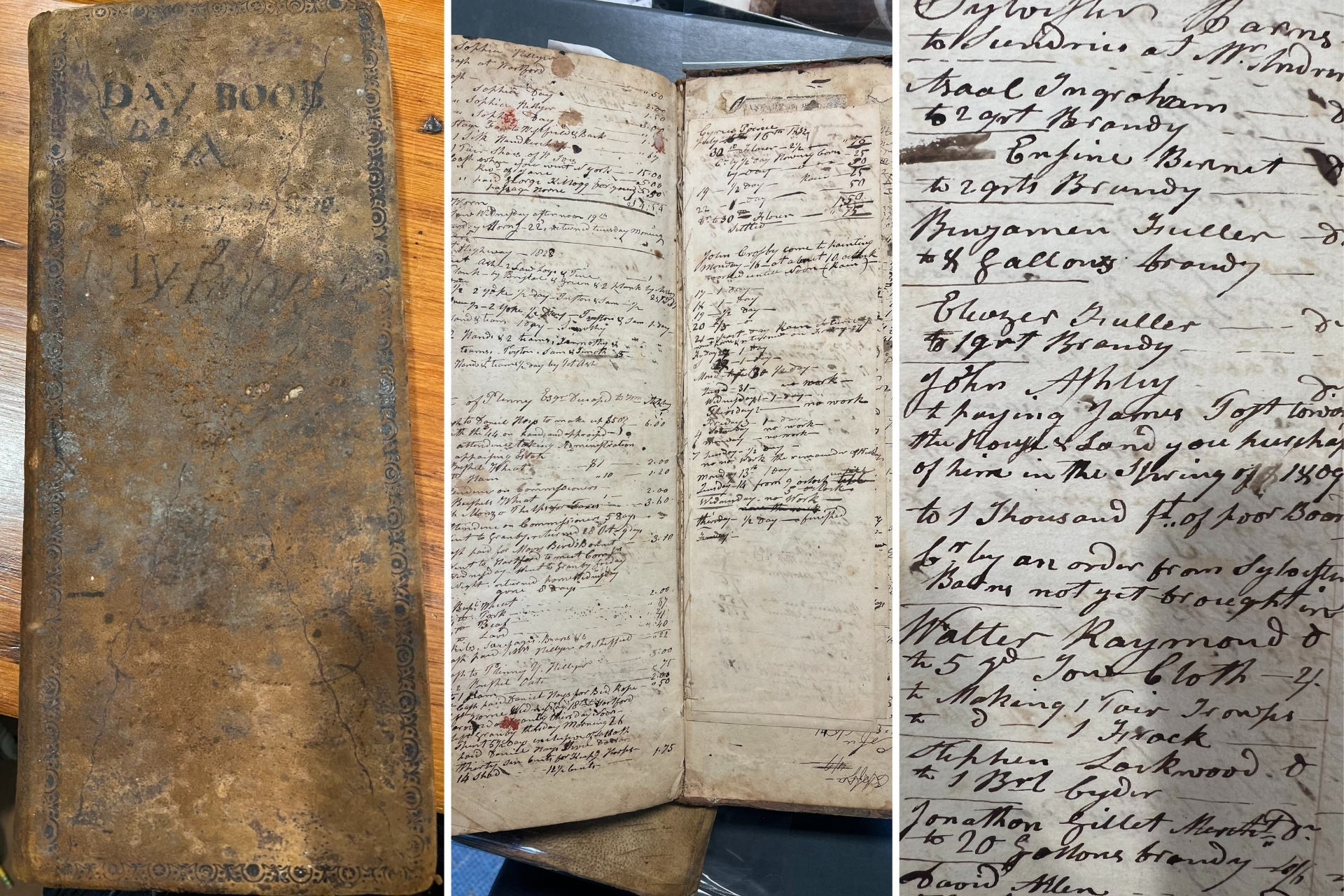

Examining New Primary Records

Some of the surviving Ashley family account books Scott analyzed.

“This work is like finding a needle in a haystack,” said Scott. “You need to know where to look and what details to look for. It takes a familiarity with regional colonial sources that requires quite a lot of time to decipher.”

The sources Scott had to get familiar with included 31 surviving Ashley family account books: 28 found in a Sheffield attic by a family descendant, and three discovered at the Ashley House in 1972 when The Trustees acquired it. Housed at the Trustees Archives and Research Center and the Sheffield Historical Society, they offer glimpses into enslaved labor in the household and beyond. An in-depth analysis of these books was paired with an expansive search of names through bills of sale, census data, court records, land deeds, local vital records, newspaper advertisements, probates, other account books, and tax records.

The materials were invaluable in helping Scott bring to life the Black community in Sheffield and the surrounding towns—including nearby New York and Connecticut—during this period. The work culminated in the discovery of new information about multiple individuals enslaved by the Ashley family who were previously unknown or who very few details were known about.

Expanding Beyond Elizabeth Freeman

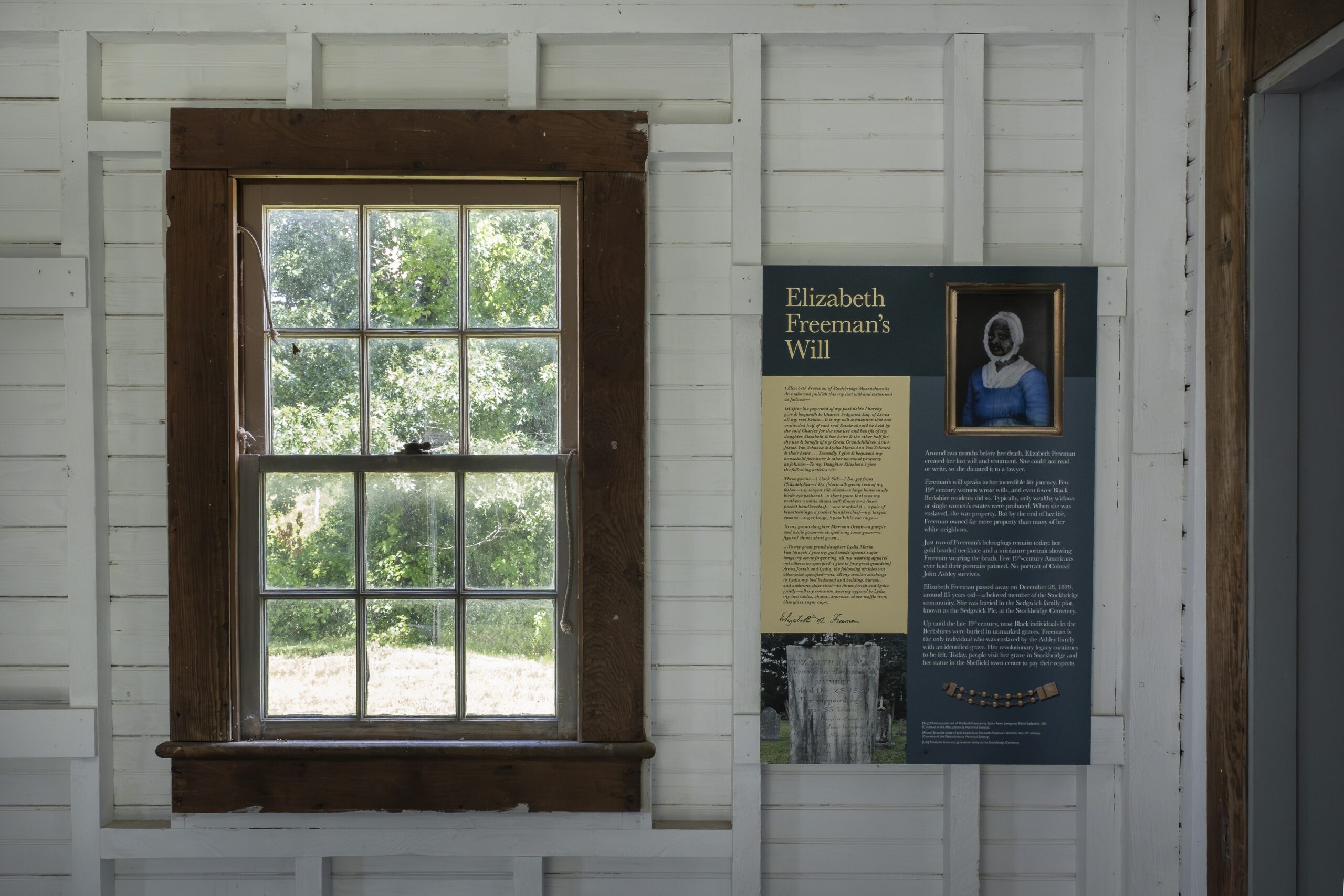

Inside the Elizabeth Freeman Room at the Ashley House in Sheffield, MA. Photo by David Edgecomb.

“The people around Elizabeth were an important part of her everyday life,” said Scott. “Understanding a clearer picture of the men, women, and children in bondage alongside Elizabeth Freeman enables a fuller conceptualization of her story.”

Individuals like Brom—who was a co-plaintiff alongside Freeman in the celebrated lawsuit against Colonel John Ashley—have become victims of anonymity despite their shared experiences. But thanks to Scott’s new research, we now know of at least five additional people enslaved by Colonel Ashley: Harry, Ceaser, Adam Mullen, Zach Mullen, and John Sheldon. Unfortunately, none of the surviving account books mention the enslaved labor of any women; Elizabeth Freeman and her daughter Betsey are only known because of the lawsuit and stories told by the Sedgwick children for whom Freeman cared for after winning her freedom.

Now, all their stories are interwoven into the Ashley House’s history. In addition to the rejuvenated Elizabeth Freeman exhibition, new panels in the home’s Elizabeth Freeman Room—what was the house’s original kitchen—celebrate the lives of everyone who was held in bondage by the Ashleys. While these are abbreviated versions of Scott’s new research, additional details can be found online in her published Commonplace Article.

Separating the Story’s Facts from Fiction

One of the refreshed panels in the Elizabeth Freeman Exhibit. Photo by David Edgecomb.

“There’s a lot of myth and misinformation around Elizabeth Freeman and her story,” said Scott. “It’s been really important to put the facts first.”

Despite all of Scott’s new research, there are still many unknowns in Freeman’s story. It’s still not clear what inspired her freedom suit. While some infer she overheard the Sheffield Resolves—a precursor to the Declaration of Independence—being drafted in the Ashley House or listened to a reading of Massachusetts’ new Constitution in 1780, there is no definitive proof of either account.

What Scott did clearly uncover is that Colonel John Ashley was not an emancipator. Even after Freeman’s court case, he was finding ways around the legal precedent to still enslave individuals, especially in the nearby states of New York and Connecticut, which didn’t outlaw slavery until 1827 and 1848, respectively. Most of the enslaved laborers at the Ashley House returned to work for Ashley.

Displayed in a dedicated building next to the Ashley House, the Elizabeth Freeman Exhibit now clarifies these details with revamped panels. And both spaces—the exhibit and the home—expound upon the stories and information previously shared with visitors for over a decade thanks to Scott’s diligent research.

Uncover the new insights in Sheffield this summer at the Ashley House and seasonally open Elizabeth Freeman Exhibit.

Tours & Events