While Christie Jackson searched one of the oldest and largest repositories of Shaker archival materials in the country maintained by The Trustees, she kept coming across one phrase: “…a good many hands…”

“It really gets to the heart of who the Shakers are, many people working together in a community forged through worship, connection to the land, commitment to sustainability, and each other,” said Jackson, Senior Curator at The Trustees.

This phrase would become the core of Jackson’s latest exhibition, “a good many hands” Shaker Communities Woven through Word, Image & Object, which is now open in the Seasonal Gallery at Fruitlands Museum. The exhibition launches during the 250th anniversary of the Shakers’ arrival in America, when they brought with them beliefs in communal living, gender and racial equality, and pacifism.

Fruitlands is only four miles away from the group’s second American settlement—the Harvard Shaker Village—which was founded in 1781 and closed in 1918. Fruitlands Museum’s founder, Clara Endicott Sears, collected materials directly from the community during its final years and opened the first Shaker Museum in the world in 1922 on the property.

“This year is a milestone anniversary, but it’s important we don’t look at this as just history because the Shakers carry on,” said Jackson. “Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in Maine continues on, and there are many Shaker advocates and friends who help carry forward and celebrate Shaker traditions and beliefs.”

A Community Centered Around “a good many hands”

When Jackson first started to explore the Shaker materials preserved at the Trustees Archives & Research Center (ARC), she didn’t know where the journey would take her. Quotes from manuscripts soon began to lift from the page and blend with personal objects and photographs, bringing together a powerful feeling of community that is central to the exhibit.

“I had such a sense of discovery when looking through all of the materials,” said Jackson. “I wanted visitors to experience that same sense of discovery and find all the ways in which you can relate to the Shakers, even if you think you can’t.”

One item that stood out to Jackson during her research was a Shaker Spool Stand (pictured above), which still has the original spools and thread from when it was given to Sears. Journals from the Shaker Sisters of Harvard, Massachusetts, talk about how they would spend long hours all gathered around such objects, sewing, mending, and weaving lively patterns of color.

“When you look at it, it just feels so busy,” said Jackson. “You can imagine several people using it with the spools spinning round…a good many hands all working together.”

A Story Told Through the “little things”

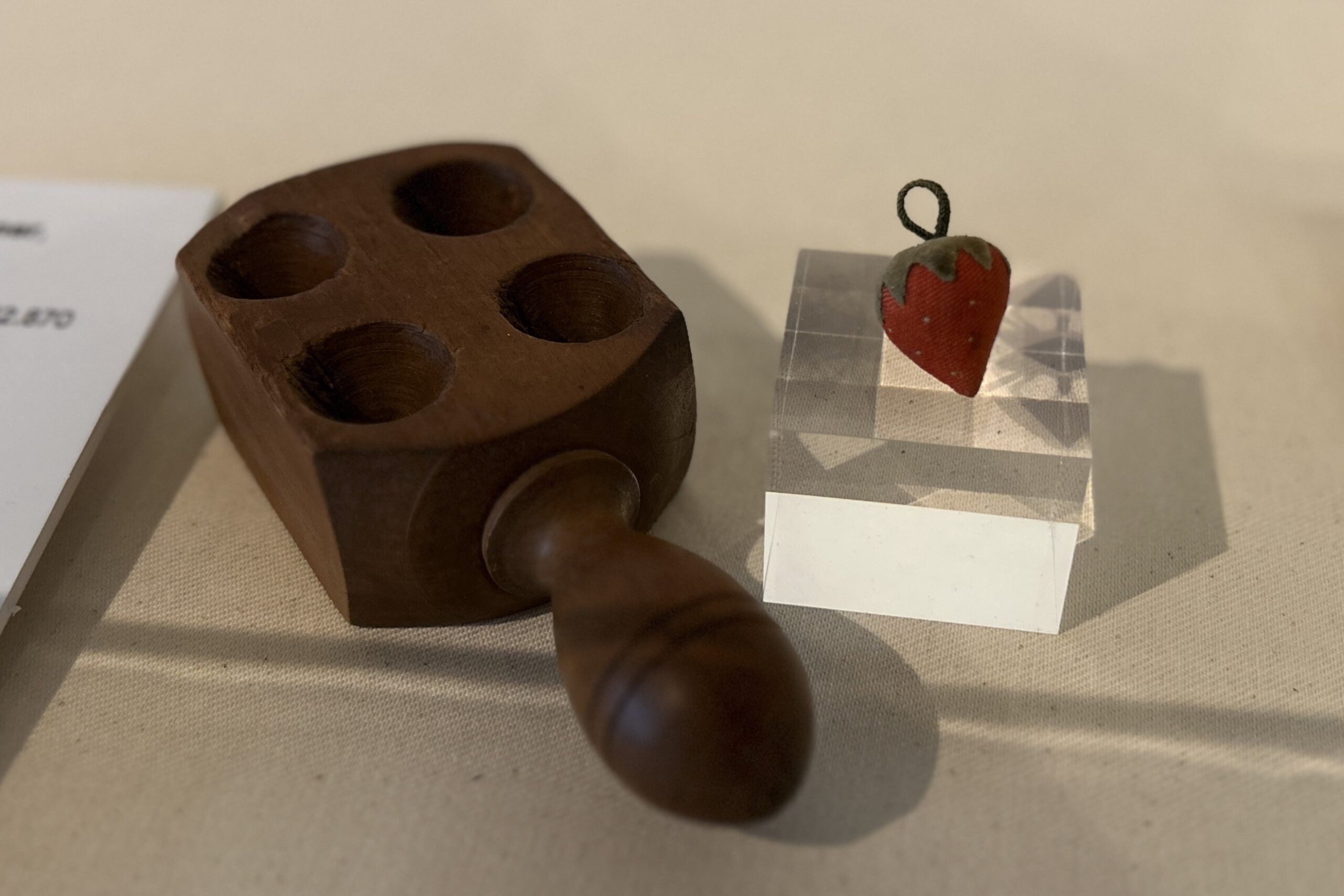

Personal objects scattered throughout the exhibition paint a vivid and relatable picture of life within the Harvard Shaker Village. An item of personal interest to Jackson is a Strawberry Needle Sharpener (picture above). This small piece of sewing equipment, barely the size of a thumb, was both used and sold by the Shakers. The brilliant colors may be dulled by time, but you can still see the complex stitching encircling the tool.

“Who doesn’t smile when you see this object?” asked Jackson. “The whole community was involved in making it, from the brothers crafting the wooden molds used to make such strawberries to the sisters intricately detailing the sharpener itself.”

Items such as this—and many other pieces of furniture and textiles on display—offer an intimate dive into the Shaker community, how community was created, and how important it can be. Whether it’s community through daily chores, friendship, art, nature, or worship, each plays an integral role in shaping who the Shakers are.

“I hope the exhibit will allow visitors to reflect on their own communities,” said Jackson. “The Shakers are still a spirited community today, and there’s so much we can draw from and bring back into our own lives.”

An Accompanying Art Installation is “anything but drab”

Across the pathway from “a good many hands” sits the Shaker Gallery, a historic building once a central part of the Harvard Shaker Village. It was relocated to Fruitlands by Clara Endicott Sears a few years after the Village closed in 1918. Now, the building is reinvigorated with a kaleidoscope of colors thanks to a new contemporary art installation by Brece Honeycutt titled “anything but drab” which accompanies the exhibition.

“Brece continues the traditions of the Shakers—specifically the use of Shaker colors and dyes—in her art,” said Jackson. “It feels like her work has always belonged in this space…it’s a perfect blend of history with modern artistic practice.”

Honeycutt’s installation coincides with a refresh of the historic objects on display in the Shaker Gallery. Many of these items haven’t been available for public viewing in years, and work in tandem with both the new artwork and larger exhibition to bring visitors into the vibrant life of the Shaker community.

Experience “a good many hands” Shaker Communities Woven through Word, Image & Object while visiting Fruitlands Museum in Harvard this summer.