A $1m grant is allowing The Trustees to quadruple the amount of Great Marsh acreage it is working to restore on the North Shore using an innovative, nature-based technique.

The funding, from the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA), expands the project to a total funded scope of 1,274 acres of marsh in Newbury, Essex, and Ipswich, and now represents the largest coastal or ecological restoration project in the 130-year history of The Trustees. The additional land funded through the grant is owned by The Trustees (689 acres), Greenbelt (141 acres), and the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife (86 acres).

“This is a real landscape-scale restoration effort using innovative restoration techniques that, prior to our work, had only been trialed on a small scale,” says Russ Hopping, Trustees Lead Coastal Ecologist. “Now, in addition to being a record-setting project for our organization, it is also one of the largest restoration projects of its type in Massachusetts. We are so grateful for the support of our partners and funders—it is collaboration like this that truly helps to advance innovative solutions that can protect our special places for generations to come.”

The three- to five-year restoration project ultimately aims to heal the natural function of the marsh, enabling it to keep pace with sea level rise using nature-based, low-impact techniques. Much of the Great Marsh ecosystem has been compromised due to ditching, an agricultural practice that continued until marsh hay farming was largely abandoned in the early 1900s, allowing the marsh to flood as the previously maintained ditch system fell into disrepair. During the Great Depression, vast re-ditching programs were launched to drain the marsh for mosquito control in areas viewed as swampy, nuisance land.

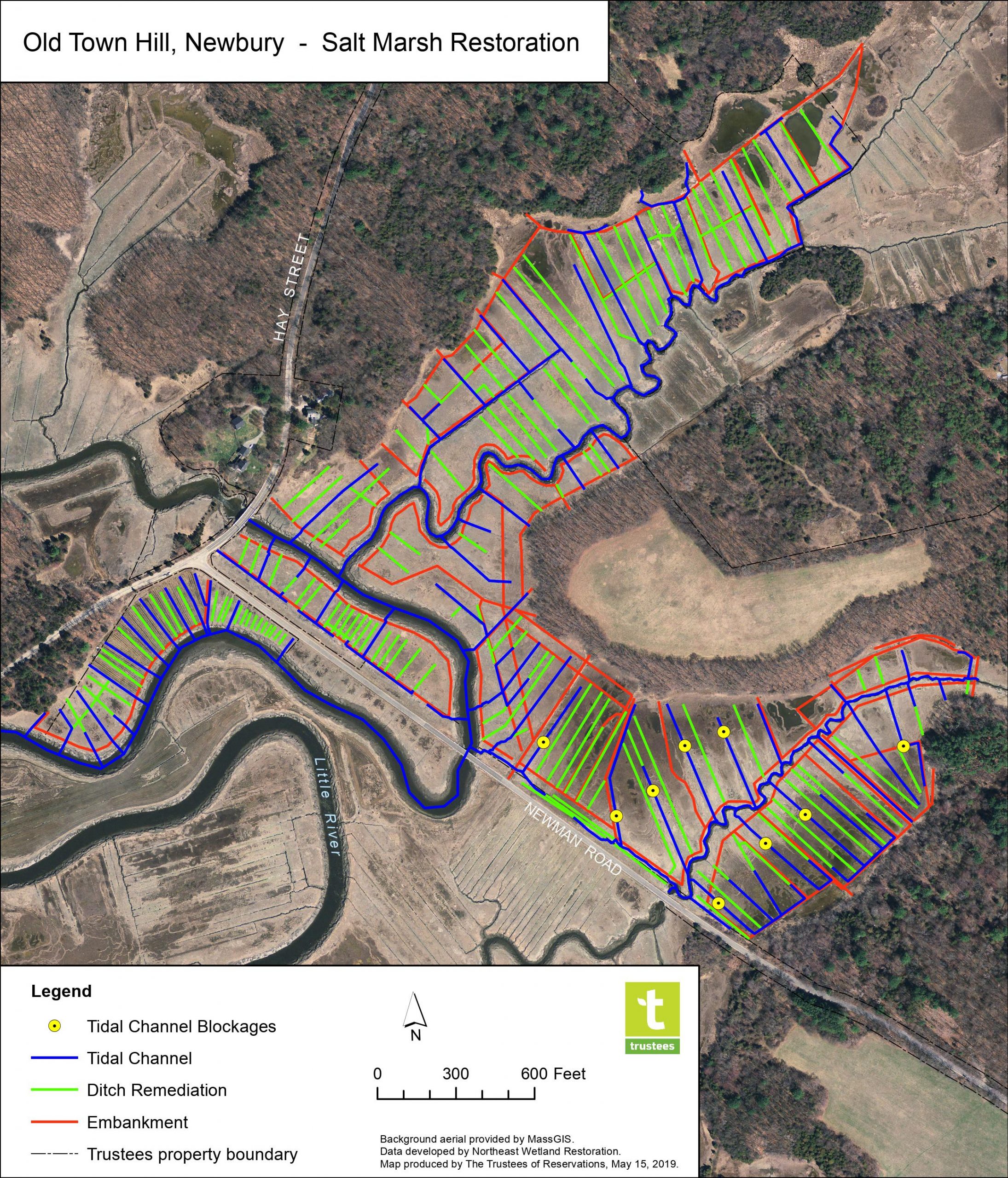

ABOVE: An aerial of Old Town Hill in Newbury shows the ditches being treated (green), blockages being cleared (yellow), tidal channels (blue) and agricultural embankments (red).

By the late 1930s, nearly 94% of New England salt marshes had been re-ditched, negatively altering the ecology of this important habitat. Today, the remnants of these ditches continue to disrupt natural tidal flow by not allowing for what should be natural draining, drowning the plants and leaving the ecosystem increasingly vulnerable to flooding and sea level rise.

The restoration technique being used by The Trustees begins with the cutting of salt marsh hay on-site, using walk-behind mowers. The hay is then gathered and secured using natural twine and stakes into the bottom of roughly 50% of the ditches. Once secured into the ditches the hay naturally traps sediment from the tides, rebuilding the salt marsh “peat” from the bottom-up. This effectively restores the marsh’s natural draining processes and increases the flow in the remaining ditches to prevent clogs and deliver much needed sediment to the surface of the marsh.

ABOVE: The restoration process involves harvesting salt marsh hay on-site, before layering it into selected ditches, loosely securing it with twine and stakes. The image above shows sediment that has accumulated in a treated ditch over the course of roughly 8 months. Circled in red is the top of a stake, barely visible.

“The natural function of a salt marsh is to flood and drain with the tides,” adds Hopping. “Natural creeks provide the right balance for un-altered salt marsh, but the widespread historic ditching was done to increase marsh drainage capacity, for better production of salt marsh hay. Now in disrepair, those ditches are clogging and flooding the marsh, allowing the land to actually ‘subside,’ or ‘sink.’ Restoring half of the ditches back to their natural function will restore balance, and the flow through the remaining ditches will keep them from clogging. It is a delicate balance.”

In 2020, an initial 300-acre restoration pilot area reached several milestones, including an April launch of restoration work at the 85-acre Old Town Hill parcel in Newbury and the start of permitting work for three parcels in Newbury, Essex, and Ipswich. A second year of restoration work began in April 2021 at Old Town Hill and is anticipated to launch next at the Crane Reservation, in Ipswich, and the Crane Wildlife Refuge, in Essex, in August 2021.

The effort to protect our marshes from rising sea level is also a fight to protect the Salt Marsh Sparrow from going extinct. This shows the work being done by @thetrustees to preserve the salt marshes⤵️@NBC10Boston @necn #ClimateAction #ClimateEmergency https://t.co/gu3mxZcIBE

— Chris Gloninger NBC10 Boston (@ChrisGNBCBoston) April 24, 2021

In addition to being an ecologically significant landscape that protects shorelines from rising sea levels and serves as a buffer to adjacent uplands from storm surge, salt marsh is critical habitat for species including the vulnerable saltmarsh sparrow. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), more than four out of every five saltmarsh sparrows have disappeared over the last 22 years—accounting for an approximate 87% drop in the population. The Great Marsh supports an estimated 5% of the species population, making it one of the most critical habitats for the species.

With the latest grant award the project has now received $1,459,411 in state and federal grants since summer 2018—including a $217,931 National Coastal Resilience Fund grant, and grants from the USFWS Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, the Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Ecological Restoration Priority Projects Program, and MassBays.

###

To learn more about “Saving the Great Marsh: Ditch Remediation, Habitat Preservation, and Resiliency Building at the Landscape Scale,” click here.