Rocky Narrows (Sherborn), The Trustees’ first reservation.

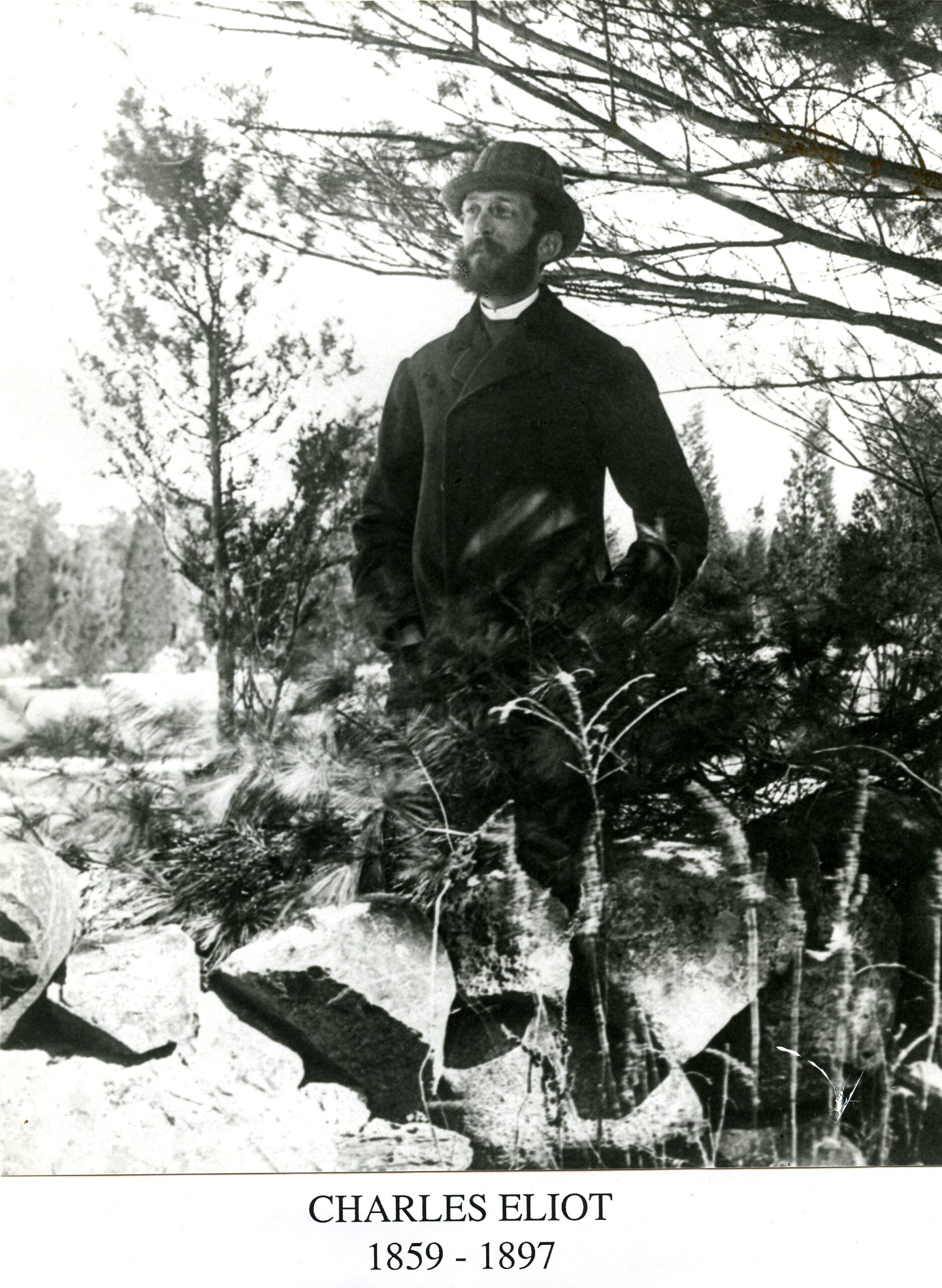

The Trustees of Reservations (today known as “The Trustees”) is a statewide preservation and conservation organization founded in 1891. Though landscape architect Charles Eliot is most often quoted as its founder, his idea was coupled with a brilliant selection of Boston’s business, health, and horticultural leaders who fostered its success. These early leaders took pleasure in the outdoor areas surrounding Boston, though these spaces were mostly unprotected and public access was not assured. With public access to open space as its goal, during its formative years, the fledgling organization focused primarily on conserving scenic landscapes and sites of historical significance. Their vision for what was valuable to save awakens the question, in our own era, of “What do we find valuable to save and why?”

For its first 75 years, the Trustees mission was to “save and maintain the beautiful and historic places of this State [Massachusetts] for the enjoyment and education of future generations.” In 1966, “places of natural beauty” were added to the mission and eventually, in 1988, “places of scenic, historic and ecological value.” Over 130 years, the focus of the organization has grown and adapted, gathering properties through donation or purchase that upheld its mission. Today, the 100,000-member organization protects over 120 properties and more than 48,000 acres of Massachusetts’ special places, including working farms, prime ecological habitat, historic buildings and landscapes, coastal beaches, and miles of hiking trails.

But in 1891, the organization’s beginnings were rooted in scenic preservation—a view from the river’s edge, a sacred historical site, and inspirational sites with famed literary associations. These were places, according to the annual report, that were threatened by being held in private ownership and rapidly disappearing.1 “It is in the self-interest of the Commonwealth to preserve, for the enjoyment of her people and their guests, all her finest scenes of natural beauty and all her places of historical interest.”2 In the eyes of the committee, these places should be withdrawn from private ownership, preserved from harm, and opened to the public “because the private ownership of such places usually results in the destruction of that special beauty of interest.”3 For the founding committee, these places were rapidly disappearing and threatened to be lost. But what examples of ‘scenes of natural beauty and places of historical interest’ did they hope to protect?

But in 1891, the organization’s beginnings were rooted in scenic preservation—a view from the river’s edge, a sacred historical site, and inspirational sites with famed literary associations. These were places, according to the annual report, that were threatened by being held in private ownership and rapidly disappearing.1 “It is in the self-interest of the Commonwealth to preserve, for the enjoyment of her people and their guests, all her finest scenes of natural beauty and all her places of historical interest.”2 In the eyes of the committee, these places should be withdrawn from private ownership, preserved from harm, and opened to the public “because the private ownership of such places usually results in the destruction of that special beauty of interest.”3 For the founding committee, these places were rapidly disappearing and threatened to be lost. But what examples of ‘scenes of natural beauty and places of historical interest’ did they hope to protect?

First, a look at the committee itself. In June 1891, a Board of Trustees, an Executive Team, and a five-member Standing Committee were formed to guide the new organization. The Standing Committee’s role was to find potential properties for acquisition and to steward the process of review, acceptance, and management. The Standing Committee included members Philip A. Chase (chairman), a prominent banker from Lynn, Charles Sprague Sargent, horticulturist, editor of Garden and Forest and director of the Arnold Arboretum, Dr. Henry P. Walcott, chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Health, and two ex officio members: Secretary Charles Eliot, landscape architect, and Treasurer George Wigglesworth, a prominent Boston business leader and president of several textile manufacturing companies in Lynn MA, Saco ME, and Manchester NH. This combination of leadership skills created a dynamic committee ready to build a process for reserving scenic and historic landscapes for public use.

Starting with Views & Waterways

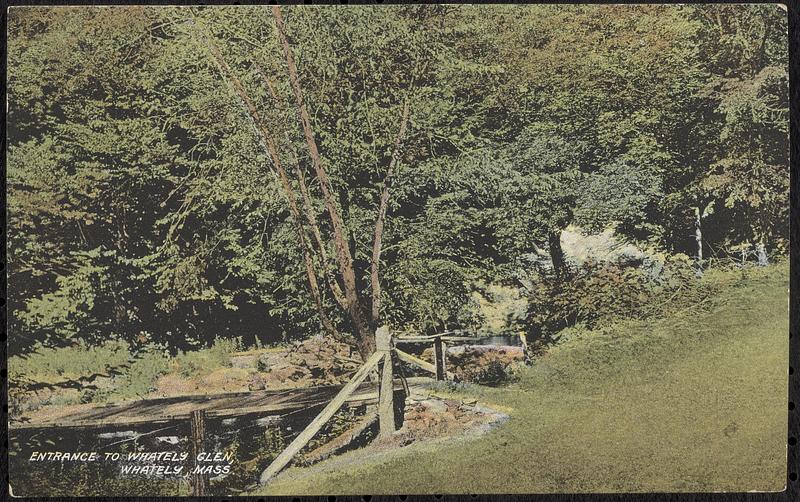

For the committee, “scenes of natural beauty” were primarily places with dramatic views or dynamic waterways. These were landscapes to be viewed, not experienced. Spots recommended to the committee for consideration included “the banks of the Charles River at Newton Upper Falls, the Falls of Beaver Brook in Belmont, the top of Shootflying Hill in Barnstable, the Purgatory in Sutton, the Glen at Whately, and the Natural Bridge near North Adams.”4 These scenes contained a viewing spot, rushing water, shoreline access, and some combination of natural elements—woodland, meadow, meandering stream—but were most valued for their beauty rather than their ecological habitat. Many gained their popularity through 19th-century New England poetry and paintings. All of these early spots of scenic beauty were acquired by Eliot’s Metropolitan District Commission.

The banks of the Charles River at Newton Upper Falls, for instance, combined the quiet wooded waters below the mill dam and the rushing waterfall spilling over the dam. A favored boating and picnicking spot, this area was one of the first saved in 1893, not by The Trustees, but instead under Charles Eliot’s other organization, the Metropolitan Park Commission (later the Metropolitan District Commission), as Hemlock Gorge Reservation. The Park Commission was organized as a publicly funded entity “to acquire, maintain, and make available to the public open spaces for exercise and recreation.” Where the proposed Trustees lands were considered as places for rest, relaxation, and inspiration, Metropolitan Park Commission lands were to be more actively experienced.

The banks of the Charles River at Newton Upper Falls, for instance, combined the quiet wooded waters below the mill dam and the rushing waterfall spilling over the dam. A favored boating and picnicking spot, this area was one of the first saved in 1893, not by The Trustees, but instead under Charles Eliot’s other organization, the Metropolitan Park Commission (later the Metropolitan District Commission), as Hemlock Gorge Reservation. The Park Commission was organized as a publicly funded entity “to acquire, maintain, and make available to the public open spaces for exercise and recreation.” Where the proposed Trustees lands were considered as places for rest, relaxation, and inspiration, Metropolitan Park Commission lands were to be more actively experienced.

Like Newton Upper Falls, Beaver Brook Falls became part of the 1893 Beaver Brook Reservation (another Metropolitan Parks reservation) to protect Charles Eliot’s Waverly Oaks, a stand of twenty-two white oaks that were estimated at the time to be 600 years old. Writer James Russell Lowell’s poem “Beaver Brook” inspired the popularization of this site. Author Robert Morris Copeland used his Beaver Brook country estate as the focus of his 1867 Country Life farm management book. Winslow Homer, who lived in Belmont for a few years, created a painting entitled Waverly Oaks to celebrate the beauty of these ancient trees. Charles Eliot himself used the preservation of the Waverly Oaks as an advocacy platform for preserving all vulnerable landscapes.

Like Newton Upper Falls, Beaver Brook Falls became part of the 1893 Beaver Brook Reservation (another Metropolitan Parks reservation) to protect Charles Eliot’s Waverly Oaks, a stand of twenty-two white oaks that were estimated at the time to be 600 years old. Writer James Russell Lowell’s poem “Beaver Brook” inspired the popularization of this site. Author Robert Morris Copeland used his Beaver Brook country estate as the focus of his 1867 Country Life farm management book. Winslow Homer, who lived in Belmont for a few years, created a painting entitled Waverly Oaks to celebrate the beauty of these ancient trees. Charles Eliot himself used the preservation of the Waverly Oaks as an advocacy platform for preserving all vulnerable landscapes.

Shootflying Hill overlooked Wequaquet Lake in Barnstable on Cape Cod. It was a favorite hunting spot for ducks and geese, but its highest value lay in its scenic vista overlooking Barnstable’s sandy hills and interconnected ponds. This hilltop is now subdivided into residential house lots with remarkable views. The Purgatory in Sutton became Purgatory State Reservation in 1919, most notable for its dramatic quarter-mile, 70-foot-deep chasm of granite bedrock. It is still managed by the Commonwealth as a state park.

Shootflying Hill overlooked Wequaquet Lake in Barnstable on Cape Cod. It was a favorite hunting spot for ducks and geese, but its highest value lay in its scenic vista overlooking Barnstable’s sandy hills and interconnected ponds. This hilltop is now subdivided into residential house lots with remarkable views. The Purgatory in Sutton became Purgatory State Reservation in 1919, most notable for its dramatic quarter-mile, 70-foot-deep chasm of granite bedrock. It is still managed by the Commonwealth as a state park.

Similarly, Whately Glen is a favored hiking and picnicking spot centered on the cascading Roaring Brook as it falls over a series of rugged rock outcroppings through the narrow valley just west of Historic Deerfield. Like Shootflying Hill, it has not been saved or chosen as a public park or reservation. In the end, none of these scenes of natural beauty were ever acquired or managed by The Trustees, but they did ground-truth the organization’s goals to protect beautiful scenery. It wasn’t until the acquisition of Monument Mountain in 1899 that views from hilltop scenery were protected by The Trustees.

Similarly, Whately Glen is a favored hiking and picnicking spot centered on the cascading Roaring Brook as it falls over a series of rugged rock outcroppings through the narrow valley just west of Historic Deerfield. Like Shootflying Hill, it has not been saved or chosen as a public park or reservation. In the end, none of these scenes of natural beauty were ever acquired or managed by The Trustees, but they did ground-truth the organization’s goals to protect beautiful scenery. It wasn’t until the acquisition of Monument Mountain in 1899 that views from hilltop scenery were protected by The Trustees.

Eyeing Historic Sites

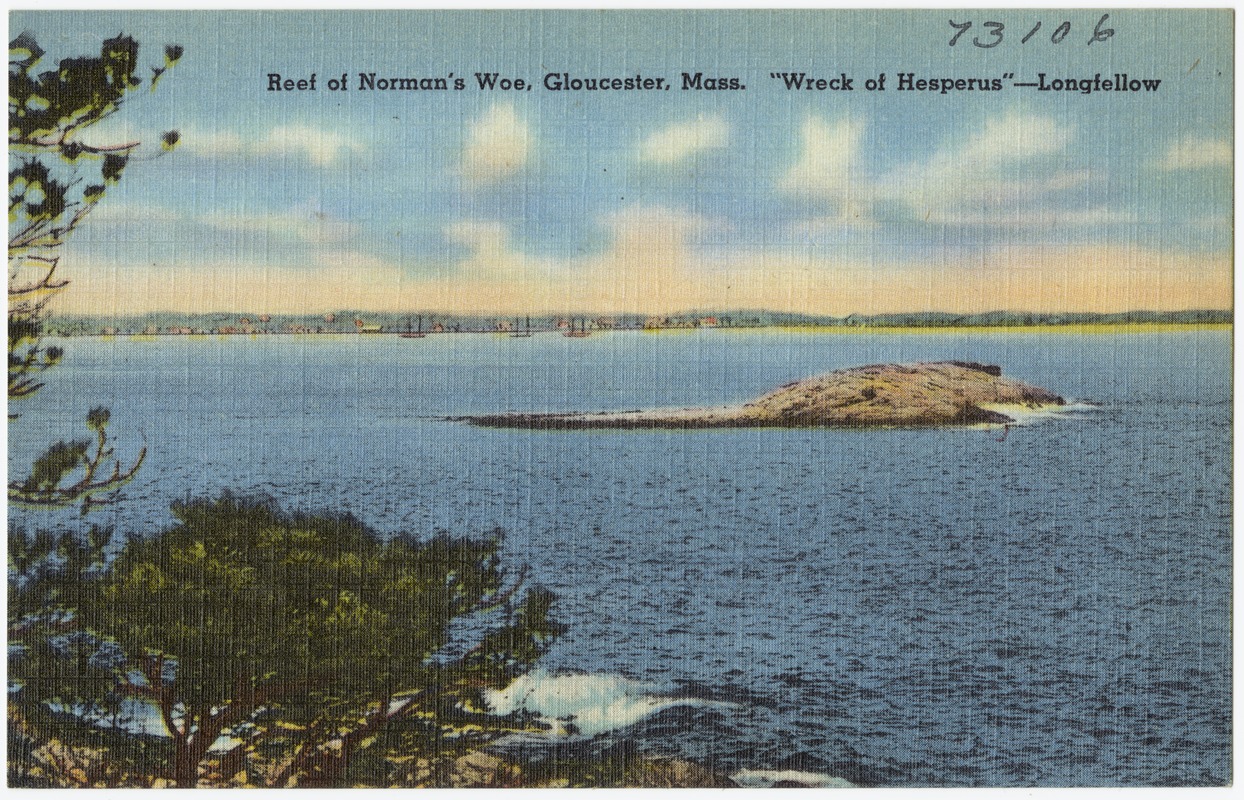

Next, the committee turned to recommended historic sites “because of their literary, romantic or historical associations.”5 The sites included archaeological sites, graves, forts, and colonial or literary landmarks. These special places were scenes without distinct boundaries, and many held legendary associations undocumented by historical facts. The recommended properties seem unrecognizable from our 21st-century perspective. The list included “the rock of Norman’s Woe near Gloucester, Heartbreak Hill in Ipswich, the Indian Cave in Medfield, the Craddock House in Medford, the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, the ‘Captain’s Well’ in Amesbury, and the well of the ‘Old Oaken Bucket’ in Scituate.” For a group of men schooled in Boston educational systems, including, for many, four years at Harvard University, this relationship between literature and landscape was born out of their classically trained academic tradition. It is no wonder that when the Trustees bylaws traveled to England to start the English National Trust in 1893, it was the hillsides and lakeshores of William Wordsworth’s Lake District that inspired that organization’s beginnings.

To better understand this relationship between literature and landscape, we need to understand why these places were so important to the Trustees founding leaders. The rock of Norman’s Woe, for instance, is a large rock sitting a few hundred feet off the western shore of Gloucester Harbor between Gloucester and Magnolia. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow memorialized the spot in his poem, The Wreck of the Hesperus, in 1840. Interestingly, Longfellow never saw this rock until many years after he wrote his poem. His literary inspiration may have, in fact, come from the wreck of the ship “Favorite” from Wiscasset ME that wrecked on this Gloucester rock in a great blizzard in 1839. The same spot was celebrated in a painting by Fitz Henry Lane in 1862, entitled Western Shore with Norman’s Woe. Local 19th-century tradition says that a man named Norman was shipwrecked and lost on the rock, but there is no historical record to substantiate the tradition.6

To better understand this relationship between literature and landscape, we need to understand why these places were so important to the Trustees founding leaders. The rock of Norman’s Woe, for instance, is a large rock sitting a few hundred feet off the western shore of Gloucester Harbor between Gloucester and Magnolia. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow memorialized the spot in his poem, The Wreck of the Hesperus, in 1840. Interestingly, Longfellow never saw this rock until many years after he wrote his poem. His literary inspiration may have, in fact, come from the wreck of the ship “Favorite” from Wiscasset ME that wrecked on this Gloucester rock in a great blizzard in 1839. The same spot was celebrated in a painting by Fitz Henry Lane in 1862, entitled Western Shore with Norman’s Woe. Local 19th-century tradition says that a man named Norman was shipwrecked and lost on the rock, but there is no historical record to substantiate the tradition.6

Despite its elusive historic significance, the rock and its scenic placement off the edge of Gloucester Harbor anchored American literature and painting to a specific location. Saving this rock outcropping would honor its poetic inspiration, but more importantly, place Gloucester Harbor and the rugged coastline of Boston’s North Shore in the category of desirable places to save and preserve for public enjoyment.

Heartbreak Hill in Ipswich was labeled in an 1832 Ipswich map as ‘Hardbrick Hill.’ This hilltop was one of the best-known outlooks along the Ipswich shoreline, offering panoramic views of Labor in Vain Creek, the Ipswich River, and the Atlantic coast. Hardbrick Hill referenced the abundance of clay and early brickworks in the area. In fact, Argilla Road, which leads to Hardbrick Hill, was named for a Greek word, argillos, meaning white clay or potter‘s earth.7 The change in nomenclature for the popular overlook was inspired by Celia Thaxter’s poem, The Legend of Heartbreak Hill, published by the Atlantic Monthly in 1873.8 The poem romanticizes a legendary love between an “Indian maiden” left behind to watch from the top of the hill for her sailor lover’s return that never came. The spectacular views and Thaxter’s poetic license spun romantic, legendary associations with the hilltop overlook. As with Norman’s Woe, there is little historical evidence to document the love affair or the hilltop overlook, but legend often creates more popularity than historical fact.

Heartbreak Hill in Ipswich was labeled in an 1832 Ipswich map as ‘Hardbrick Hill.’ This hilltop was one of the best-known outlooks along the Ipswich shoreline, offering panoramic views of Labor in Vain Creek, the Ipswich River, and the Atlantic coast. Hardbrick Hill referenced the abundance of clay and early brickworks in the area. In fact, Argilla Road, which leads to Hardbrick Hill, was named for a Greek word, argillos, meaning white clay or potter‘s earth.7 The change in nomenclature for the popular overlook was inspired by Celia Thaxter’s poem, The Legend of Heartbreak Hill, published by the Atlantic Monthly in 1873.8 The poem romanticizes a legendary love between an “Indian maiden” left behind to watch from the top of the hill for her sailor lover’s return that never came. The spectacular views and Thaxter’s poetic license spun romantic, legendary associations with the hilltop overlook. As with Norman’s Woe, there is little historical evidence to document the love affair or the hilltop overlook, but legend often creates more popularity than historical fact.

The Indian Cave in Medfield did not have literary affiliations like the others, but instead marked a well-known low opening in the rocky ledges of what is now Westwood. This opening, sometimes called Oven Mouth, leads to a long tunnel that ends in a large cave opening. The site is an easily shown example of indigenous land use and occupation positioned from a European Colonial viewpoint. Poised near a series of stream and pond outflows from Buckminster Pond, this spot is embedded in historic and archaeological associations of its earliest inhabitants and is still marked with a historical marker to this day.9

The Indian Cave in Medfield did not have literary affiliations like the others, but instead marked a well-known low opening in the rocky ledges of what is now Westwood. This opening, sometimes called Oven Mouth, leads to a long tunnel that ends in a large cave opening. The site is an easily shown example of indigenous land use and occupation positioned from a European Colonial viewpoint. Poised near a series of stream and pond outflows from Buckminster Pond, this spot is embedded in historic and archaeological associations of its earliest inhabitants and is still marked with a historical marker to this day.9

Medford’s Craddock House is an example of the earliest years of cultural contact between indigenous cultures and European settlement. The house was thought to have been built in 1634 by Matthew Craddock, but contemporary architectural research dates the house a bit later. Nevertheless, late 19th-century historians incorrectly named the building as the oldest brick house in America (it may be the earliest gambrel-roofed house in the country). Also known as the “Fort” and the “Old Garrison” because of its thick walls and portholes, it holds the same tenuous histories of habitat and defense as many early New England structures. Almost destroyed in the 1880s, the house was bought, remodeled, and eventually made famous on the 1892 city seal of Medford. Instead of being acquired by The Trustees, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (founded in 1910 and now called Historic New England) acquired the house.10 Like the Cave, the Craddock House presented the opportunity to own a bit of contact-period Massachusetts history that was quickly disappearing.

Medford’s Craddock House is an example of the earliest years of cultural contact between indigenous cultures and European settlement. The house was thought to have been built in 1634 by Matthew Craddock, but contemporary architectural research dates the house a bit later. Nevertheless, late 19th-century historians incorrectly named the building as the oldest brick house in America (it may be the earliest gambrel-roofed house in the country). Also known as the “Fort” and the “Old Garrison” because of its thick walls and portholes, it holds the same tenuous histories of habitat and defense as many early New England structures. Almost destroyed in the 1880s, the house was bought, remodeled, and eventually made famous on the 1892 city seal of Medford. Instead of being acquired by The Trustees, the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (founded in 1910 and now called Historic New England) acquired the house.10 Like the Cave, the Craddock House presented the opportunity to own a bit of contact-period Massachusetts history that was quickly disappearing.

The Wayside Inn in Sudbury had been a tavern and inn long before it was memorialized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, The Wayside Inn in 1863. The poem was part of a larger anthology, Tales from a Wayside Inn, written as a series of poetic voices of visitors staying at the inn for the night. This anthology included his famous Paul Revere’s Ride. These poems, like those that memorialized Norman’s Woe and Heartbreak Hill, spun a legendary history not entirely rooted in historical fact that still clings to the Wayside Inn today. Henry Ford, who famously said that “history is bunk,” bought the Wayside Inn in 1923, turning it into a historic attraction that included other structures moved to the site. The Inn was gutted by fire in 1955 and quickly restored by the Ford Foundation.

The Wayside Inn in Sudbury had been a tavern and inn long before it was memorialized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, The Wayside Inn in 1863. The poem was part of a larger anthology, Tales from a Wayside Inn, written as a series of poetic voices of visitors staying at the inn for the night. This anthology included his famous Paul Revere’s Ride. These poems, like those that memorialized Norman’s Woe and Heartbreak Hill, spun a legendary history not entirely rooted in historical fact that still clings to the Wayside Inn today. Henry Ford, who famously said that “history is bunk,” bought the Wayside Inn in 1923, turning it into a historic attraction that included other structures moved to the site. The Inn was gutted by fire in 1955 and quickly restored by the Ford Foundation.

Certainly, lesser known than the Wayside Inn, John Greenleaf Whittier’s 1890 poem, The Captain’s Well, built a literary legend around a small public well that still stands in front of Amesbury’s Middle School. The wells legend says that Capt. Valentine Bagley II, a ship’s carpenter, built the well in Amesbury shortly after his return home, after his ship was stranded on the Coast of Arabia in 1792 and the crew had to walk into the Arabian Desert to find help. Of the 34 that started the journey, only eight survived, including Bagley, who vowed never to have anyone thirst for water again. Whittier’s poem recounts in detailed verse the digging of the well, Bagley’s travails, and his noble civic endeavor to provide fresh water to any passerby. At the time the poem was written, the well had fallen into disrepair, but by the late 1890s was rejuvenated and connected to the town’s water system and protected by a wooden structure.11 Later, the wooden structure was replaced by a large stone monument engraved with Whittier’s poem. Today, the well and its monument still stand as a local Main Street landmark in Amesbury.

Certainly, lesser known than the Wayside Inn, John Greenleaf Whittier’s 1890 poem, The Captain’s Well, built a literary legend around a small public well that still stands in front of Amesbury’s Middle School. The wells legend says that Capt. Valentine Bagley II, a ship’s carpenter, built the well in Amesbury shortly after his return home, after his ship was stranded on the Coast of Arabia in 1792 and the crew had to walk into the Arabian Desert to find help. Of the 34 that started the journey, only eight survived, including Bagley, who vowed never to have anyone thirst for water again. Whittier’s poem recounts in detailed verse the digging of the well, Bagley’s travails, and his noble civic endeavor to provide fresh water to any passerby. At the time the poem was written, the well had fallen into disrepair, but by the late 1890s was rejuvenated and connected to the town’s water system and protected by a wooden structure.11 Later, the wooden structure was replaced by a large stone monument engraved with Whittier’s poem. Today, the well and its monument still stand as a local Main Street landmark in Amesbury.

Finally, the well of the ‘Old Oaken Bucket’ in Scituate was a popular tourist attraction by 1891. Poet Samuel Woodworth crafted a lament for the lost days of youth entitled “The Old Oaken Bucket,” which he published in New York in 1817.12 The poem quickly became a popular success and was translated into more than eight other languages. Born in Scituate in 1784, Woodworth lost his mother at the age of twelve and moved to the farm with the Old Oaken Bucket when his father remarried in the late 18th century. Hot and thirsty from working the farm, Woodworth often drank from the well. A decade after the poem was published, it was set to music by George Kiallmark and, in 1834, published under another tune as “The Old Oaken Bucket / A Favorite Scotch Song”. “The old oaken bucket, the iron-bound bucket, / The moss-covered bucket which hung in the well” was the lyrical refrain. The song stayed a folk song standard until 1941, when Bing Crosby reawakened its popularity and recorded the tune with Woodworth’s full lyrics.13 More recently, folk singers like Tom Roush have recorded the ballad. The Scituate house and its well were saved by the Town of Scituate and are managed by the Scituate Historical Society, open to the public. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 for its architectural evolution.14 Woodsworth’s brief residency predated the construction of the current farmhouse, and later alterations of the building continued into the 1930s. Nevertheless, the popularity of Woodworth’s poem and its use for song lyrics throughout the 19th and 20th centuries has kept the property a cultural icon. Postcards, plates, a Currier and Ives lithograph, and other commemorative memorabilia cemented this cultural icon in our American landscape.

Finally, the well of the ‘Old Oaken Bucket’ in Scituate was a popular tourist attraction by 1891. Poet Samuel Woodworth crafted a lament for the lost days of youth entitled “The Old Oaken Bucket,” which he published in New York in 1817.12 The poem quickly became a popular success and was translated into more than eight other languages. Born in Scituate in 1784, Woodworth lost his mother at the age of twelve and moved to the farm with the Old Oaken Bucket when his father remarried in the late 18th century. Hot and thirsty from working the farm, Woodworth often drank from the well. A decade after the poem was published, it was set to music by George Kiallmark and, in 1834, published under another tune as “The Old Oaken Bucket / A Favorite Scotch Song”. “The old oaken bucket, the iron-bound bucket, / The moss-covered bucket which hung in the well” was the lyrical refrain. The song stayed a folk song standard until 1941, when Bing Crosby reawakened its popularity and recorded the tune with Woodworth’s full lyrics.13 More recently, folk singers like Tom Roush have recorded the ballad. The Scituate house and its well were saved by the Town of Scituate and are managed by the Scituate Historical Society, open to the public. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996 for its architectural evolution.14 Woodsworth’s brief residency predated the construction of the current farmhouse, and later alterations of the building continued into the 1930s. Nevertheless, the popularity of Woodworth’s poem and its use for song lyrics throughout the 19th and 20th centuries has kept the property a cultural icon. Postcards, plates, a Currier and Ives lithograph, and other commemorative memorabilia cemented this cultural icon in our American landscape.

Recognizing Other Places of Deep Meaning

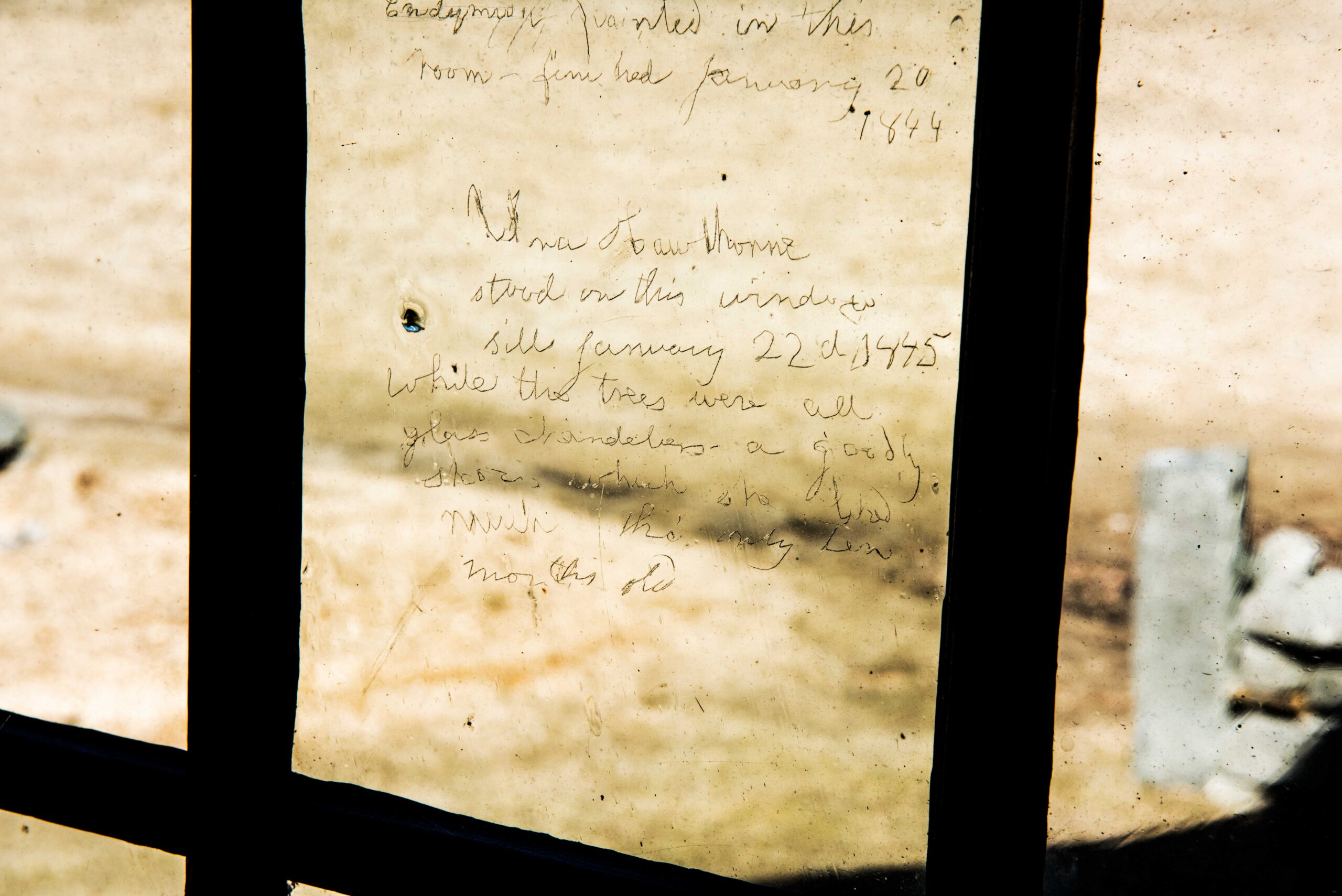

A messaged etched onto the window of The Old Manse. © David Kasabian

It is these highly revered late 19th-century literary illusions to Massachusetts landmarks that topped the list of potential Trustees reservations. If all had come to The Trustees as desired, the organization’s role in the historic preservation movement might have been more widely recognized. Like the remarkable natural views from mountaintop or turbid shoreline, The Trustees hoped to preserve these places for public enjoyment and to tie Massachusetts’ earliest historical figures, artists, and writers to its best landscapes. “There is a need, too, that the value of historical and literary memorials be recognized before they are injured or destroyed,” wrote the Standing Committee in 1892.15

Given that Eliot was an ex officio member of the Standing Committee and the Secretary of the Corporation, we might attribute these words to him, yet the annual summary was signed by all five members of the Standing Committee. In 1896, the Committee reflected on Charles Eliot’s vision at his death: “Charles Eliot found in this community a generous but helpless sentiment for the preservation of our historical and beautiful places. By ample knowledge, by intelligent perseverance, by eloquent teaching, he created organizations capable of carrying out his great purposes and inspired others with a zeal approaching his own.” In many ways, Charles Eliot’s writings continue to inspire the work of The Trustees today, making many of their reservations, such as The Old Manse in Concord or the William Cullen Bryant Homestead in Cummington, places of legendary appeal.

Given that Eliot was an ex officio member of the Standing Committee and the Secretary of the Corporation, we might attribute these words to him, yet the annual summary was signed by all five members of the Standing Committee. In 1896, the Committee reflected on Charles Eliot’s vision at his death: “Charles Eliot found in this community a generous but helpless sentiment for the preservation of our historical and beautiful places. By ample knowledge, by intelligent perseverance, by eloquent teaching, he created organizations capable of carrying out his great purposes and inspired others with a zeal approaching his own.” In many ways, Charles Eliot’s writings continue to inspire the work of The Trustees today, making many of their reservations, such as The Old Manse in Concord or the William Cullen Bryant Homestead in Cummington, places of legendary appeal.

In its earliest years, the Standing Committee remained most interested in the historic scene and its literary and artistic connections. Capturing both access and visibility to these scenes was paramount if they were to be saved for public enjoyment, yet they recognized that places of deep meaning could range beyond history and literature. “As the years pass,” wrote the Standing Committee, “a variety of motives will be found to inspire the giving of lands into the care of the Trustees. Some givers will look to perpetuate the attractiveness that is the source of the prosperity of all pleasure resorts. Other gifts will spring from the laudable desire to preserve some of the geological, botanical, or archaeological wonders of the land. Some will have their origin in the wish to hand down to posterity unchanged those scenes which have been consecrated by the lives of artists, seers, or poets; and yet others will embody the philanthropic purpose of those who would give crowded populations an opportunity to view the beauty of the fair natural world.”16

Natural Beauty, History, & Literary Memorials

The Trustees eventually did get scenes of natural beauty and historical or literary memorials. Mrs. Fanny Foster Tudor offered twenty acres in Stoneham, entitled Virginia Wood, in 1891 in memory of her daughter. Two thousand dollars were collected to care for the property, but the young organization had not yet proven its systems for managing these gifts of land. In 1894, Virginia Wood was transferred to become part of the Metropolitan District Commission’s Middlesex Fells, a large area of woodland and wetland surrounding a series of ponds between Melrose, Stoneham, and Winchester in Boston’s northwestern suburbs. It stays today at the heart of this reservation, a popular hiking and dog walking destination.

Monument Mountain in Great Barrington was the organization’s first hilltop, described as “a prominent and picturesque feature of the landscape, and the views from it are among the most beautiful in these far-farmed hills.”17 Monument Mountain, in fact, held both natural beauty and literary association. On a summer hike in August 1850, Herman Melville, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Nathaniel Hawthorne hiked Monument Mountain. A surprise thunderstorm forced the group to shelter in a small cave and discuss their literary projects, including Melville’s ideas for Moby Dick.18 Monument Mountain is still part of The Trustees portfolio, a popular and active destination for recreational hiking today. Recently, The Trustees work with the Stockbridge-Munsee Community has recognized the mountain’s significance to Indigenous cultures of the region, including the renaming of some of its trail names to reflect its sacred ethnographic values more respectfully.

Monument Mountain in Great Barrington was the organization’s first hilltop, described as “a prominent and picturesque feature of the landscape, and the views from it are among the most beautiful in these far-farmed hills.”17 Monument Mountain, in fact, held both natural beauty and literary association. On a summer hike in August 1850, Herman Melville, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Nathaniel Hawthorne hiked Monument Mountain. A surprise thunderstorm forced the group to shelter in a small cave and discuss their literary projects, including Melville’s ideas for Moby Dick.18 Monument Mountain is still part of The Trustees portfolio, a popular and active destination for recreational hiking today. Recently, The Trustees work with the Stockbridge-Munsee Community has recognized the mountain’s significance to Indigenous cultures of the region, including the renaming of some of its trail names to reflect its sacred ethnographic values more respectfully.

The first place of historical association was obtained in 1898 on Minton Hill in Milton. Hutchinson Field is a ten-acre parcel along the banks of the Neponset River that once belonged to Massachusetts colonial governor Thomas Hutchinson. John M. Forbes and his sister, Mrs. Mary F. Cunningham, donated three-quarters of the land, and the rest, a part of the former Russell family estate, was acquired by member subscriptions for $31,250, “to which the public owe the preservation of a view of both picturesque and historic interest,” wrote the Standing Committee in 1899. The colonial governor’s estate had covered substantial acreage and was subdivided and gifted to patriotic soldiers after the Revolutionary War. By the late 18th century, it had developed into wealthy family homes fueled by the prosperous shipping industry. A distinctive feature of the original estate is a long ha-ha wall, now found nearby on the grounds of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church. The wall, a feature of many 18th-century English estates, picturesquely separated livestock from the estate’s pleasure grounds. The ten-acre Hutchinson Field is still managed by The Trustees. It captures not only a piece of this historic estate but, most importantly, protects a beautiful view northeast to downtown Boston across the shores of the Neponset River.

The first place of historical association was obtained in 1898 on Minton Hill in Milton. Hutchinson Field is a ten-acre parcel along the banks of the Neponset River that once belonged to Massachusetts colonial governor Thomas Hutchinson. John M. Forbes and his sister, Mrs. Mary F. Cunningham, donated three-quarters of the land, and the rest, a part of the former Russell family estate, was acquired by member subscriptions for $31,250, “to which the public owe the preservation of a view of both picturesque and historic interest,” wrote the Standing Committee in 1899. The colonial governor’s estate had covered substantial acreage and was subdivided and gifted to patriotic soldiers after the Revolutionary War. By the late 18th century, it had developed into wealthy family homes fueled by the prosperous shipping industry. A distinctive feature of the original estate is a long ha-ha wall, now found nearby on the grounds of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church. The wall, a feature of many 18th-century English estates, picturesquely separated livestock from the estate’s pleasure grounds. The ten-acre Hutchinson Field is still managed by The Trustees. It captures not only a piece of this historic estate but, most importantly, protects a beautiful view northeast to downtown Boston across the shores of the Neponset River.

Places of literary association came much later. The home of William Cullen Bryant in Cummington was offered to The Trustees in 1899, but the Standing Committee could not accept it until funds were provided to ensure its long-term support. Finally, in 1927, the family bequeathed the property and the necessary financial support to The Trustees, becoming the first property of a literary association to come to the organization.19 It was named a National Historic Landmark in 1966.

Places of literary association came much later. The home of William Cullen Bryant in Cummington was offered to The Trustees in 1899, but the Standing Committee could not accept it until funds were provided to ensure its long-term support. Finally, in 1927, the family bequeathed the property and the necessary financial support to The Trustees, becoming the first property of a literary association to come to the organization.19 It was named a National Historic Landmark in 1966.

The Old Manse, in Concord, where nascent writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne launched their literary careers, was acquired by the organization with a $17,500 purchase in 1939.20 Donors to the acquisition fund included none other than John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who had begun his preservation of Historic Williamsburg, VA only a decade before. “[The Old Manse] marks one of the most historic places in the country,” wrote the Standing Committee in 1938, “We hope that we may be able to save it, as an inspiration for those who visit it to do their part, however small, in the fight for individual freedom, which in these days is being attacked from so many angles.”21 The property became a National Historic Landmark in 1966 and remains open to the public for regularly scheduled tours of the house and grounds.

The Old Manse, in Concord, where nascent writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne launched their literary careers, was acquired by the organization with a $17,500 purchase in 1939.20 Donors to the acquisition fund included none other than John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who had begun his preservation of Historic Williamsburg, VA only a decade before. “[The Old Manse] marks one of the most historic places in the country,” wrote the Standing Committee in 1938, “We hope that we may be able to save it, as an inspiration for those who visit it to do their part, however small, in the fight for individual freedom, which in these days is being attacked from so many angles.”21 The property became a National Historic Landmark in 1966 and remains open to the public for regularly scheduled tours of the house and grounds.

The Core of the Trustees Mission

Though none of the earliest sites ever made it into the list of Trustees reservations, the terms ‘beautiful and historic places’ or ‘natural beauty and historic places’ were core to The Trustees mission from 1891 to 1989. As such, the organization continued to seek properties rich in scenic beauty and historic association. Beauty, scenery, history, and public access remain key to the organization’s work today.

It was not until 1989, in anticipation of the organization’s centennial, and two decades after the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970 and its subsequent legislative acts to protect habitat and ecological spaces that a new mission was crafted, “dedicated to preserving for public use and enjoyment properties of exceptional scenic, historic and ecological value for public use and enjoyment.” The expanded wording recognized the emergence of the American ecological movement in the 1960s and 1970s, and its distinct separation from the historic preservation movement that successfully passed the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966. Since then, the Trustees of Reservations became a recognized leader in ecological habitat and land protection, while its work in historic and scenic preservation remains part of its core values.

Ever nimble, The Trustees holds the unique mission of enfolding ‘scenes of beauty,’ historical properties, and ecological habitat for the enjoyment of many. The genius of its Standing Committee—a banker, an industrialist, a business leader, a horticulturist, a landscape architect, and a doctor—was foundational to the organization’s ability to think broadly, innovate, adapt, and remain relevant over multiple generations. Guided by bits of natural scenery and places of historic interest, The Trustees survives as the oldest preservation and conservation organization in the United States, as Eliot’s “museum of landscapes” continues to grow.

Show your support for The Trustees by becoming a Member—or renewing your Membership—today!

Memberships1Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1892; 31-32

2Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1892; 29

3Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1892; 31-32

4Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1891; 14

5Ibid.

6Cape Ann Museum. Online catalog entry Western Shore with Norman’s Woe, 1862 by Fitz Henry Lane accessed January 11, 2023

7“The Legend of Heartbreak Hill.” Historic Ipswich on the Massachusetts North Shore accessed on January 11, 2023

8Ibid. Atlantic Monthly published version of the poem

9This cave opening is sometimes referred to as ‘Oven Mouth’; Accessed on January 12, 2023

10Peter Tufts House. Accessed on January 12, 2023

11“The Captain’s Well” Macy-Colby House, Amesbury MA. Accessed on January 11, 2023

12Oaken Bucket Homestead. Accessed on January 12, 2023

13https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AySh-O3Ezy0 Accessed on January 12, 2023

14MACRIS Scituate SCI 119 “Woodworth Farm”; 1996

15Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1892; 34

16Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1892; 15

17Trustees of Public Reservations. Annual Report 1899; 21

18Barbara Basbanes Richter. “Melville’s Meeting of the Minds on Monument Mountain.” July 2014. Fine Books and Collections Newsletter. Accessed on January 20, 2023

19John Woodbury to Mary C. Olmsted. Dec. 19 1899. Library of Congress. Olmsted Associate Records. Project number 02050.

20Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1938; 13

21Trustees of Public Reservations Annual Report 1938; 13