BNAF board members leave a Highland Park community garden on June 11, 1981

“To fully appreciate the Fund’s assistance for community gardening in Boston you should really see the gardens and talk with gardeners.” So wrote Eugenie Beal, the President of the Boston Natural Areas Fund (BNAF) in May 1981 to her fellow board members. In 1977, Beal along with four collaborators, Norman Byrnes, Richard Fowler, Cecile Gordon, and Katharine Kane (who was Mayor Kevin White’s deputy mayor at the time), had founded the organization specifically to protect the “urban wilds” of Boston. Now only a few years later, community gardeners were starting to reach out to the organization for support as they attempted, similarly, to protect their gardens as open spaces. This was an opportunity for those curious to learn more about gardening in the “Boston inner city,” she wrote, closing: “Do come.”

The tour of June 11th, 1981, once hidden, opens a window into an emerging coalition of urban conservation in Boston. Due to the Trustees merger with the Boston Natural Areas Network in 2014, the Archives & Research Center inherited a wide-ranging collection of unprocessed administrative records, correspondence and project files, as well as a large visual collection of approximately 18,000 slide images and 7,000 photographs.

In 2023, the Trustees received a National Endowment for the Humanities grant for this project. For the past six months, a team has worked to make these visual materials publicly available under this NEH grant, arranging, describing, and preparing these images for digitization with the help of an outside vendor. After completing this preliminary stage of processing, we can reflect upon one of the more striking series of photographs that this collection has to offer: that of an emerging preservation alliance in the Highland Park area of Roxbury.

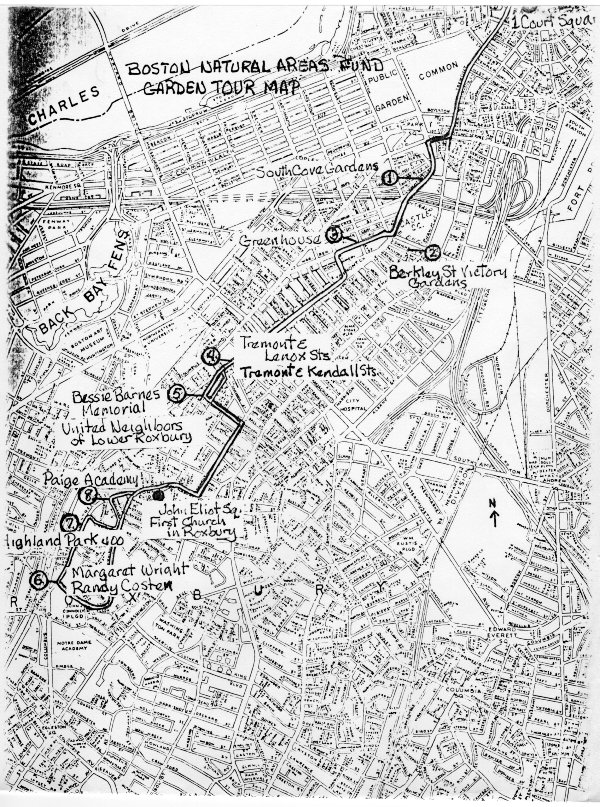

An annotated map of the Boston Natural Areas Fund tour. Boston Natural Areas Network collection. The Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

Rebirth of a Neighborhood

“In 1981, Roxbury’s Highland Park neighborhood was dubbed ‘The Arson Capital of the Nation” (p.31). In Streets of Hope, Peter Medoff and Holly Sklar document the struggles that the whole Roxbury neighborhood confronted at the cusp of the 1980s, continually subject to redlining, disinvestment, abandonment, and increasingly also arson-for-profit schemes.

But community activists and leaders of Roxbury also foresaw opportunities to reclaim empty and blighted lots in their neighborhood for the benefit of the entire community. According to Medoff and Sklar, community organizing through nonprofit agencies such as the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative proved both instrumental to creating a new model of community-supported land trust. In Highland Park, on the other hand, attention turned to reviving and integrating the open spaces within the fabric of the existing community, especially promoting the need to protect these open and green spaces from real estate speculation and development of housing.

Boston Natural Areas Fund’s Tour of Roxbury’s Community Gardens

On June 11, 1981, the staff, board, and supporters of BNAF accepted Eugenie Beal’s challenge, boarding a bus at Chinatown’s South Cove Community Garden to begin their tour of Roxbury’s emerging network of gardens. Conveniently, the bus drove past the long-standing Berkeley Community Garden, where Chinese and Lebanese immigrants had first cultivated those vacant lots more than a decade ago. The first stop, however, would not be until Lower Roxbury to see the Lenox-Kendall Community Gardens, one of whose founders and coordinators, Charlotte Kahn, was joining them on the tour. Five years prior, Kahn and others worked to clear the debris and prepare the lots alongside Tremont Street. Now, from empty lots, they could witness a thriving community garden.

Charlotte Kahn introduces two board members to the Bessie Barnes Community Garden

Cecile Gordon (pictured left), a BNAF co-founder, speaks with others on Windsor Street in Lower Roxbury

Partnerships in the Making …

On Warwick Street, parallel to Tremont Street, the bus parked, and everyone disembarked to visit a series of gardens that Lower Roxbury neighbors had reclaimed from debris of demolished lots. One of these gardens, significantly, was the Bessie Barnes Garden.

In 1979, a request from concerned neighbors addressed the newly hired BNAF executive director John Blackwell, asking for assistance in purchasing the demolished lots at 28 Warwick Street. They intended to perpetuate the garden in memory of a local activist named Bessie Barnes, whom they knew as the “Mayor of Greenwich Street.” Across the street, with funding assistance through the city of Boston’s Revival Program, the Bessie Barnes Community Garden was becoming established.

There, BNAF also met with the local organization United Neighbors of Lower Roxbury and visited a garden that neighbors had started on a vacant lot on Shawmut Avenue, before everyone boarded the bus again for their next destination, Highland Park.

Highland 400 Survival Garden

Here in Boston, Edward Cooper became a leader in community gardening movement both city-wide and in this community. With Kahn, Cooper helped to form the nonprofit Boston Urban Gardeners. A former director of the NAACP, Cooper locally focused upon gardening particularly to organize elderly neighbors in his own community of Highland Park. On Linwood Street, across from his home, Cooper envisioned the Highland 400 Survival Garden. Once the site of three houses, the empty lot offered an opportunity to build community. For Ed Cooper, as he would tell historian Sam Bass Warner in 1987, the purpose was to give the neighborhood’s elderly a sense of purpose. “I think, over and above getting those people out of the house has been the conviviality that exists when they come out here. They do a little hoeing, they sit down, they chat, they talk about things, and they meet other people. Which gives them, in my opinion, an opportunity to think that, ‘although I’m 75, I’m somebody. I’ve got a place to go to garden, and I’ll meet some friends out there.’”

As the garden grew, bringing hope to the community, challenges persisted. The gardeners needed to contend with lead contamination in the soil. They also needed the city to supply water to garden. In addition, the threat of development loomed. The Boston Redevelopment Authority had slated the garden as a proposed site for new housing. Cooper inquired with the BNAF whether they could assist.

Concerned neighbors and local activists, at the same time, became the ones to guide advocacy and the priorities for preservation and the use of open space in this changing approach This tour event on June 11, 1981, was not the first, nor the last time that BNAF was welcomed to Highland Park. From correspondences in the archive, there is also a letter from Ed Cooper himself, who requests that the BNAF purchase the empty lots at 1-3 Linwood Street for the permanent benefit of the neighborhood. John Blackwell accepted. Currently, the site known as Kittredge Green, this open space is one of the parks that the Trustees manage in the Highland Park neighborhood.

The BNAN slide collection also includes an even earlier series of images from July 1979, when executive director John Blackwell led a tour of Highland Park that included its urban wilds, the Frederick Law Olmsted designed park on the top of Fort Hill, as well as new community gardens that had begun to spring up in vacant and abandoned lots such as gardens on Fort Avenue, which would become later known as the Margaret Wright Memorial Garden.

In the BNAN slide collection, we have also found a later series of approximately fifty slides – many intimate portraits – from April 8, 1988, when Ed Cooper, neighbors, and BNAF staff convened in the living room of Cooper’s house on Linwood Street to discuss design proposals.

A New Coalition in the New Boston

What is the BNAN collection, and the photographs of this 1981 tour particularly, telling us? As records, these images help to show the growing commitment of the BNAF to help gardeners protect their community spaces. In 1982, the organization began to collaborate with coordinators to protect and manage community gardens. By 1984, the City of Boston would transfer the deeds of sixteen community gardens to BNAF. Additionally, their work would become no longer limited to solely land acquisition, as the organization increasingly played the role of making and facilitating connections with other community-based advocacy efforts. For instance, a guest on this tour Caleb Loring (pictured below) would in a year’s time become one of the organization’s next presidents.

The Boston Natural Areas Network, arguably, is the city’s most impactful proponent of urban open spaces in the latter part of the 20th and the early 21st century. Although its initial focus was protecting urban wilds, its mission expanded to include community gardens. By 2014, with its merger with the Trustees, the organization owned and managed over fifty community gardens as well as seven urban “pocket-parks” and the City Natives nursery. This advocacy would continue with the advocacy and community organizing for the Neponset River and East Boston greenway projects that sought to connect urban wilds and to bring Bostonians in closer relation to the harbor and the green spaces that surround them. The slides in the BNAN collection illustrates this development of the organization’s mission and what it has meant for the communities the organization has served.

Most importantly, as this series of photographs show us, the organization’s mission gained a new focus in aligning with partner organizations as it sought to promote and provide support for community gardens. The organization was no longer simply a “Fund,” it was a network. In 1981, notably, BNAF purchased on behalf of the Highland 400 Survival Garden the 8,000 square foot lot as well as an adjacent lot to secure the permanency of this community-building project. Today, in Highland Park, the legacy of Cooper’s is alive and well at the Edward L. Cooper Gardening and Education Center.

Ed Cooper, Charlotte Kahn, and future BNAF president Caleb Loring, and un unidentified woman talk, left to right

We are just getting started, learning what this collection has to tell us about local grassroots organizing and the key partnerships that helped preserve open spaces in the city of Boston. In the months ahead, while we await the digitization of these 25,000 images, the staff at the Archives & Research Center will continue work in the BNAN archive with the goal of opening this collection for the public in the spring of 2025. In the meantime, all of us will do well to heed Eugenie Beal’s invitation to become more curious about what urban gardening can cultivate.