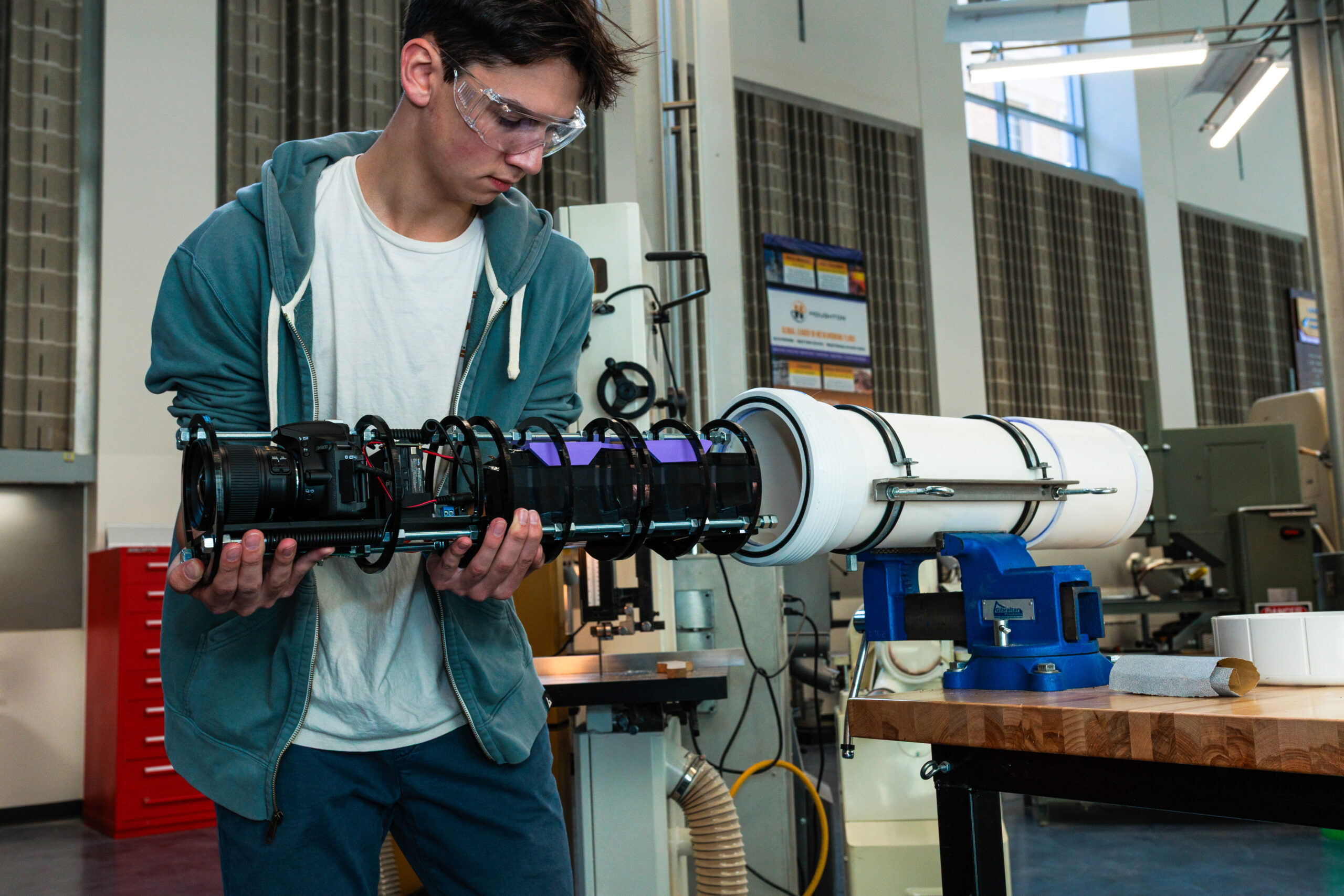

Soren Goldsmith assembles an IMPACT camera trap. Photo by Russell Laman/National Geographic

Soren Goldsmith is changing the way we document the natural landscape. A 2024 National Geographic Young Explorer, and 2025 grantee from National Geographic, he is deep into his project entitled “Project Marshlight,” documenting and telling the stories of Massachusetts’ coastal marshes, including the Great Marsh in Ipswich.

Goldsmith has developed IMPACT, first-of-their-kind devices (aquatic camera traps) that allow motion-activated captures underwater. These camera traps allow for quality images of wildlife to be taken without disturbance. Designed for researchers, photographers, and explorers, IMPACT devices are creating new ways to document and understand aquatics ecosystems.

We sat down with Soren to learn more about his work thus far with IMPACT devices, what he learned while working on the Great Marsh, and what the future holds for Project Marshlight and IMPACT.

A timelapse of the tide at the Great Marsh taken by IMPACT.

Can you introduce yourself and tell us about your National Geographic Young Explorer Project? Can you explain your camera trap technology?

My name is Soren Goldsmith. I’m a National Geographic Explorer, wildlife photographer, and engineering student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. My project is dedicated to illuminating the salt marshes of Massachusetts to raise a sense of urgency for their conservation.

The primary output of this project is the development and implementation of an innovative underwater motion activated camera. This allows us to photograph wildlife in the marsh without disturbing it.

The biggest engineering hurdle was the motion sensor. Traditional land-based camera traps use infrared sensors that detect heat, like the warmth of a coyote walking by (when warmth is detected the camera takes a photo). The problem is, water effectively blocks infrared signals, so those sensors are useless when submerged. If I wanted a camera trap that worked underwater, I needed a different approach.

My system uses a visible light sensor, similar to how a regular camera works. It constantly analyzes the pixels in the frame, comparing them to the split-second before. If the pixels change significantly, like when a fish swims by, the system recognizes the movement and triggers the camera. This technology has the potential to revolutionize underwater documentation, allowing us to study, understand, and connect with elusive wildlife, especially species that are disappearing.

What drew you to study the Massachusetts coast, specifically salt marshes?

Salt marshes are vital. They prevent erosion, store carbon, and support some of the state’s most biodiverse ecosystems. However, they are rapidly disappearing due to human development and sea-level rise. One thing I love about salt marshes is that they are urban ecosystems; they can exist right up against a city, yet feel completely wild. While this makes them accessible for people to visit, the wildlife still remains hard to find. My goal is to put a spotlight on these hidden creatures, and help locals connect with the marsh, hopefully inspiring a sense of urgency to conserve it.

When I started in wildlife photography, I focused on what was around me: urban ecosystems. Growing up in an urban Massachusetts town, the wildlife closest to me was urban. I noticed how hard it was to find wildlife in my town, and how my neighbors didn’t feel a strong connection to nature either.

My first project explored urban forests with terrestrial camera traps, but I soon looked for a new challenge, and the salt marsh was the clear standout. These ecosystems desperately need our help. Not only do they harbor incredibly unique and disappearing wildlife, but they also have faced significant legal and permitting hurdles that make conservation difficult.

That created a massive opportunity. A key theme in all my work is taking something misunderstood or unseen and flipping the narrative to reveal its true value. Salt marshes were the perfect candidate to do exactly that.

A photo captured by Goldsmith of a Horseshoe Crab in the Great Marsh

Why the Great Marsh? In studying the Great Marsh in comparison to marshes in Wellfleet, what did you notice was the same? What was different?

The Great Marsh stood out to me because of the incredible stewardship of The Trustees. Having the opportunity to go out with Russ [Editor’s Note: Russ Hopping is The Trustees’ Lead Coastal Ecologist, primarily responsible for work on the Great Marsh and surrounding Areas] gave me a firsthand look at effective conservation in action, seeing not just what is being done now, but what’s possible for the future.

It also offered a fascinating contrast to my work further south in Wellfleet, on the Cape. Wellfleet is teeming with diamondback terrapins and fiddler crabs. But as you move north to the Great Marsh, the ecosystem shifts. There are no terrapins, and fiddler crabs are rare, having only recently migrated that far north.

Beyond biology, I chose the Great Marsh because of its scale, proximity to urban development, and conservation needs. Because so many people already visit Crane Beach, the landscape feels familiar to many in Massachusetts. That familiarity makes it easier for people to connect with the work, because the place already feels personal to them.

What do you hope to do with the data you collected? In that same vein, what is the next step for this technology? Do you see future applications for areas like the Great Marsh?

My goal is to share these images with the people of Massachusetts and anyone living near a salt marsh. These photos offer a rare glimpse into an ecosystem that is close to home but seldom seen, especially beneath the surface. I have already seen how imagery can inspire people to visit the marsh and contribute to its conservation, and I hope this work reaches as many people as possible.

Beyond the images, I see a lot of potential in the technology itself. I have been dedicating my recent efforts to refining the underwater camera trap to make it more accessible. I want researchers, photographers, and conservationists worldwide to have this tool for data collection and storytelling. This represents a new wave in conservation technology: a way to observe remote underwater environments for long periods, completely unattended and without human interference.

There are still so many stories to tell, especially here in the Great Marsh. The reality is, we don’t know half of what exists beneath these waters. This technology finally gives us the chance to find out.

What is one of your favorite memories of working on the Great Marsh during this project, or one of your favorite things you gleaned from your camera traps?

One of my favorite memories from the project happened a few months in. I had deployed the camera trap in an estuary river bend where I’d noticed a lot of horseshoe crab activity. When I returned two weeks later to check the data, I found plenty of standard shots, but then I saw something incredible.

One crab had crawled right up onto the camera housing, giving me a rare view of its legs working from below. Then, as it turned to leave, it whipped its tail around, churning up the water. I captured this epic, close-up shot of that jagged, prehistoric-looking tail surrounded by the bubbles. It was a moment that could only happen because the animal wasn’t worried about me; it was just doing its thing, completely undisturbed, while the camera quietly watched.