Helen entertaining guests on the brick terrace at Ashdale Farm, c. 1950. Image courtesy of The Trustees of Reservations Archives & Research Center, The Stevens-Coolidge Place Collection.

A curator’s dream is when material—the objects and architecture in a collection—and the archival—documents, diaries, and other written records—coalesce to tell a fuller, more accurate story. When it comes to the Stevens-Coolidge House, this serendipity happens more often than we hope! After Helen Stevens and John Gardner Coolidge married in 1909, they set off on a married life full of travel, collecting antique furniture and decorative arts, and renovating the beloved Stevens family home in North Andover: Ashdale Farm. Just as exciting as the stories within each New Hampshire-made secretary or Chinese porcelain vase are the plentiful archives and “Thinkbooks,” or diaries, that John and Helen wrote together throughout their married life.

Helen and John on their wedding day, April 16, 1909, on the old wooden terrace at Stevens-Coolidge. Image courtesy of The Trustees of Reservations Archives & Research Center, The Stevens-Coolidge Place Collection.

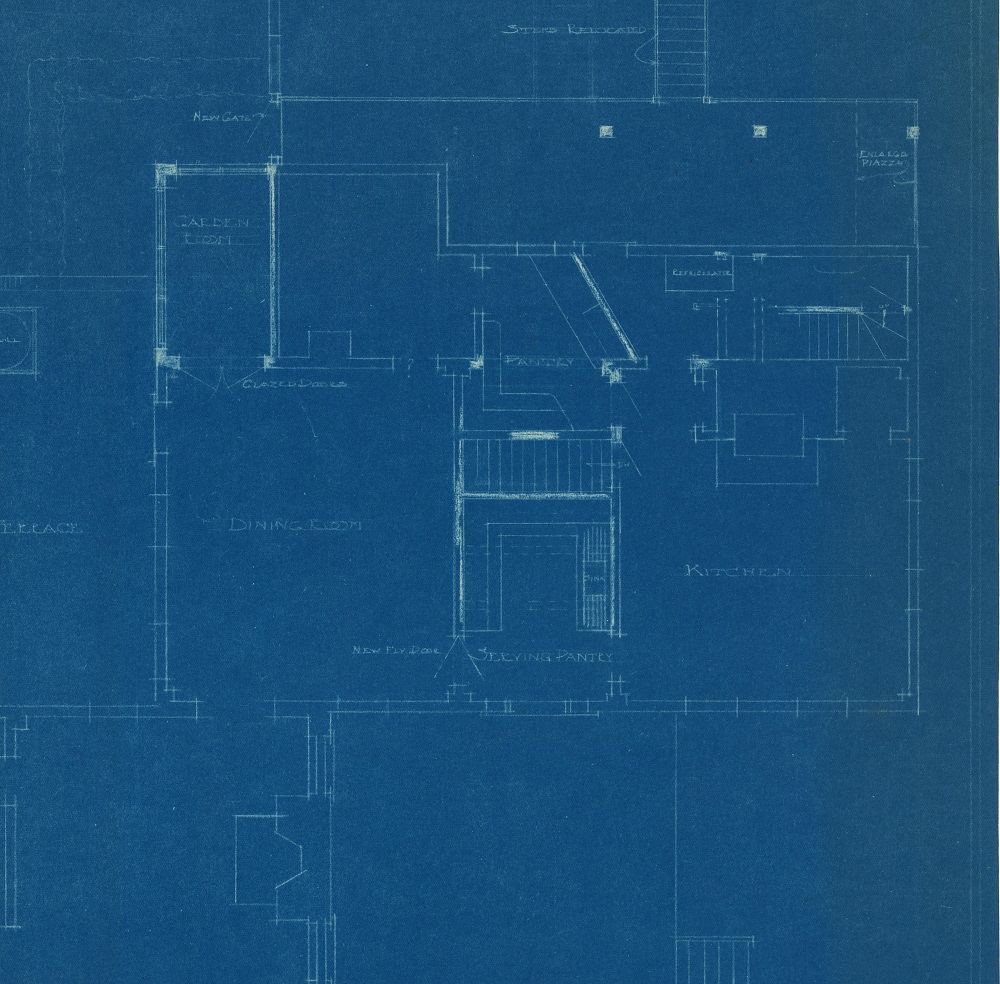

One of the highlights of the Stevens-Coolidge Place collection in The Trustees Archives & Research Center are the many blueprints of the main house. While undated, they are signed by preservation architect Joseph Everett Chandler, whom Helen and John hired after visiting the House of Seven Gables in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1914. The Coolidges had a vision to transform the Stevens family home in North Andover from a rambling Victorian family farmhouse into a paragon of Colonial Revival architecture and design. Although both wings of the house post-date the Colonial period, Helen and John felt that one of the best ways to connect with their shared Anglo-American heritage was to renovate their home to reflect their taste and ancestry.

The blueprints and Thinkbook entries tell a story not only of collaboration between architect and client, but also of cross-class management. Chandler descended from generations of Massachusetts-born Anglo-Americans, but he was never a member of Boston’s social elite. Most of Chandler’s clients, whether the project was a public museum or private residence, were wealthy, entitled, and accustomed to giving orders. This first blueprint, featuring a glassed-in room that overlooked the gardens and provided direct access to outdoor living spaces, was rejected. We know this design must have been one of the earliest as the result was a double-depth Dining Room featuring a Dutch style door that could be opened fully or just at the top for fresh air and garden views.

Early blueprint of Chandler's proposed renovations to the main house at Stevens-Coolidge; note the "GARDEN ROOM" in the back left corner and angled extra-large pantry. Neither of these spaces made it into the final design. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations Archives & Research Center, Stevens-Coolidge Place Collection.

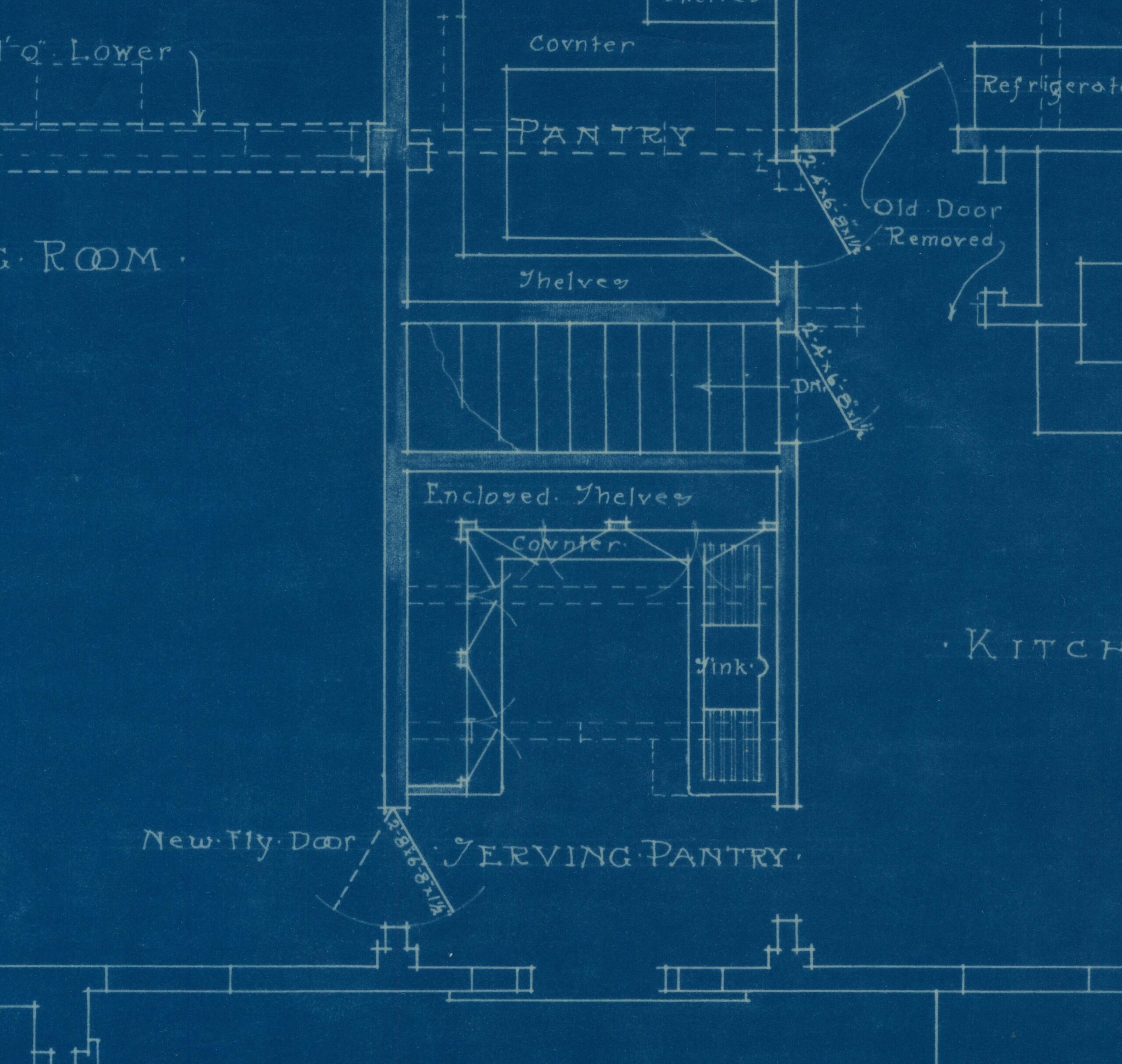

Chandler’s blueprints also reveal specific elements of the home’s layout prior to his renovation. Faint dotted lines appear in different areas of the house, indicating where walls, windows, and doors would need to be removed or altered to realize Chandler’s design. Most notable is the staircase removal from the back wing of the house, allowing Chandler to design and install a Butler’s Pantry for easier service during lunch parties and removing old walls above it to create one large space rather than an upstairs hall and bedrooms.

Chandler’s talents extended beyond the arrangement of walls and windows, however, into the realms of color and design—and it is here where we can see how he managed his entitled clientele. Cost was a recurring concern for John, and he noted in their Thinkbook that the plans “are attractive but we fear very expensive [because] he wants to paint the house white.”1 When John went to confront Chandler, however, he was unsuccessful in changing the architect’s mind: “the result [of our meeting] was satisfactory for one of the amiable and intelligent traits in his character is that he never says no to any suggestion, [but] if he does not like it he seeks to divert it by oblique opposition.”2 After several months of considering painting the house white, and one afternoon of attempting to alter Chandler’s plans, John gave up on trying to save money on the exterior paint and acquiesced to Chandler’s vision.

Close-up of blueprints of first floor. The dotted lines inside the "SERVING PANTRY" show old walls and supports for the former front hall staircase. Image courtesy of The Trustees of Reservations Archives & Research Center, The Stevens-Coolidge Place Collection.

Helen and John left for Paris shortly after finalizing the blueprints with Chandler. Over the next three years, the renovation at Ashdale Farm was entirely in Chandler’s hands. New research reveals that Chandler’s impact on the house was far more holistic than previously imagined: photographs from the late 1890s and early 1920s reveal how each room was furnished before and after Chandler’s work. However, we needed the expert help of conservator Christine Thomson to investigate the wallpaper and paint colors from these black and white photos. With her help, we uncovered Chandler’s deep involvement in all phases of the project—including his hand-picked choices of pale green wallpaper in the Library—one of the largest entertaining spaces—and a blush pink in the Morning Room. The colors, textures, and patterns Chandler incorporated throughout the home, including in the formal gardens, guided how the Coolidges furnished and used each space both inside and outside of the house’s wooden walls.

The Library at Stevens-Coolidge after Chandler's renovation, 1918-1923. Photograph from album BL4. Image courtesy of The Trustees of Reservations Archives & Research Center, The Stevens-Coolidge Place Collection.

The Library at Stevens-Coolidge in 2021, showing the newly-installed wallpaper in original colors as chosen by Chandler. Image courtesy of Katharine F. Grant, Curatorial Fellow.